Click here to download the full paper (PDF)

Authored By: Dr. Syed Faraz Akhtar, Assistant Professor, ICFAI Law School, ICFAI University, Tripura,

Click here for Copyright Policy.

ABSTRACT:

This study examines the overlooked nexus between husbands’ psychological distress, endured emotional abuse, and marital dissolution in contemporary India. It contends that systemic invisibility – sustained by biased media narratives and exclusionary legal frameworks – exacerbates mental health crises among married men, accelerating family breakdown. The research pursues three objectives: (1) to critically analyze representations of marital conflict in Indian print/digital media (2018–2024), (2) to synthesize empirical data on abuse prevalence and mental health outcomes among husbands, and (3) to propose evidence-based legal and social interventions. Methodologically, it employs critical discourse analysis of 100+ news reports from prominent publications (Times of India, The Hindu, India Today) alongside systematic review of secondary datasets (NCRB suicide statistics, NFHS-5 mental health gaps, and NGO case archives). Key findings indicate that media narratives predominantly frame wives as victims (82% of sampled articles), rendering husbands’ emotional suffering nearly invisible. Quantitative analysis reveals emotional abuse tactics – including legal coercion (Section 498A IPC threats), financial control, and public shaming – correlate strongly with clinical depression in 71% of documented cases. Crucially, 63% of marital suicides involve husbands facing false allegations or prolonged abuse. The study concludes that institutional erasure of male trauma within India’s gender-skewed legal ecosystem (notably the DV Act 2005) transforms private anguish into societal crisis. It advocates for gender-neutral domestic violence legislation, mandatory mental health assessments in family courts, and national awareness campaigns challenging toxic masculinity norms. By exposing this “silent collapse”, the research advances equitable policy solutions for marital distress.

Keywords: Spousal Mental Health, Marital Abuse Dynamics, Media Framing Bias, Legal Gender Asymmetry, Matrimonial Legislation Reform, Male Suicide Epidemiology.

I. INTRODUCTION: THE UNSEEN EMERGENCY:

CONTEXT: A CONCEALED PUBLIC HEALTH CRISIS:

A severe and largely unaddressed public health issue is emerging in modern India: the escalating prevalence of psychological distress among married men.[1] National mortality statistics reveal an alarming trend, with married males constituting 70% of all suicides explicitly connected to marital strife. Familial conflict is identified as the primary catalyst in nearly two-thirds (64%) of these tragic outcomes.¹ This surge in self-inflicted deaths points to a profound institutional failure to identify and support husbands who may be experiencing spousal abuse and mental health crises. Deeply ingrained cultural expectations that equate masculinity with emotional invulnerability—exemplified by the maxim mard ko dard nahi hota (“men don’t feel pain”)—combined with legal structures that do not recognize male victimization, have effectively silenced this suffering in public conversation and policymaking.

PROBLEM: SYSTEMIC INVISIBILIZATION

THIS CRISIS IS PERPETUATED BY THREE INTERCONNECTED SYSTEMIC FACTORS:

- Cultural Stigmatization: Dominant societal norms that define vulnerability as a weakness,[2] impose significant social penalties, actively discouraging help-seeking behaviors among men in distress.

- Statutory Marginalization: Foundational legal measures, specifically the gender-specific Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act (2005)[3] and Section 498A of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) [4] legally preclude husbands from being classified as victims, creating a protection gap for male survivors of abuse.

- Clinical Neglect: Mental healthcare infrastructure lacks standardized protocols for detecting trauma in male patients stemming from spousal abuse,[5] resulting in widespread diagnostic oversight.

This triad of neglect converts private agony into a public health emergency, where divorce often becomes the sole visible indicator of a prolonged personal breakdown.

RESEARCH OBJECTIVES:

This study is designed to:

- Decipher Media Narratives: Conduct a critical examination of how Indian media portrays husbands in divorce reporting (2018–2024) to measure biases and mechanisms of omission.

- Synthesize Empirical Evidence: Integrate data from the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) on suicides, mental health indicators from the National Family Health Survey-5 (NFHS-5), and case records from non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to determine the prevalence of abuse and its psychosocial consequences.

- Advocate for Gender-Inclusive Reforms: Formulate evidence-based policy recommendations for legal, healthcare, and public discourse systems to ensure they address the suffering of all individuals.

This investigation challenges the prevailing notion that victimhood in marriage is exclusively a female experience, arguing for trauma-informed approaches that acknowledge the distress of husbands.

II. MEDIA ANALYSIS: THE PORTRAYAL OF HUSBANDS IN INDIAN DIVORCE REPORTING (2018–2024):

Scope of Analysis

This research examined 138 news articles from leading Indian publications between 2018 and 2024 to assess media representations of husbands in marital disputes. Sources encompassed:

- Newspapers: The Times of India, The Hindu, The Indian Express

- Magazines: India Today, The Week, Savvy

- Online Platforms: Scroll.in, The Quint, and blogs from government-registered men’s rights groups[6]

Methodology

Employing Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA)[7] – a technique that investigates the relationship between language and power dynamics—the study evaluated:

- Terminology: The specific language journalists used to characterize husbands (e.g., “perpetrator” versus “victim”).

- Narrative Framing: Whether articles recognized the emotional challenges faced by husbands.

- Sourcing: Which viewpoints were predominantly featured in the reporting.

Key Findings

| Issue Analysed | Finding | Evidence |

| Portrayal as Victims | A mere 17% of articles acknowledged husbands experiencing abuse or psychological distress[8] | Phrases such as “husband’s suicide note cited constant humiliation by wife” appeared in only 23 of the 138 articles. |

| Stereotypes | 78% of crime reports featured headlines that presumed the husband’s guilt before any trial[9] | Example: “Greedy husband arrested for dowry torture” (published prior to judicial proceedings)[10] |

| Mental Health Gap | 89% of articles addressed wives’ emotional pain, whereas only 11% covered husbands’ trauma[11] | Wives’ conditions were often medicalized (e.g., “depression”); husbands’ distress was frequently labelled as “anger issues.” |

| Policy Influence | 92% of articles discussing the DV Act quoted women’s groups; only 11% cited men’s advocates[12] | This media bias correlates with zero gender-neutral amendments to the DV Act between 2018 and 2023[13] |

Significance Of Findings:

Indian media acts as an institutional silencer[14] by:

- Omitting Male Suffering:Overlooking the experiences of husbands who endure emotional abuse.

- Perpetuating Bias:Utilizing language that presupposes men are invariably the aggressors.

- Influencing Legislation:sidelining male perspectives in policy discussions, thereby fostering public acceptance for legal systems that exclude husbands as potential victims of abuse.[15]

Demonstrated Media Influence

- Quantifiable Narrative Bias:

A quantitative assessment confirms that 83% of Indian media outlets consistently portray marital conflict through a simplistic victim-perpetrator lens:

- Wives are depicted as victims in 89% of divorce-related reports.[16]

- Husbands are characterized as aggressors in 78% of headlines covering domestic disputes.[17]

- Societal Consequences of Biased Framing:

This imbalance in representation:

- Diminishes public acknowledgment of abused husbands by 71% (according to survey)[18]

- Reinforces cultural stigma, which deters help-seeking (only 12% of distressed husbands reach out to NGOs)[19]

- Impact on Policy:

Media bias linked with institutional inaction:

- Zero gender-neutral provisions were incorporated into the DV Act (2005) during the 2018–2024 study period[20]

- Parliamentary documents indicate that less than 5% of debates on divorce law referenced the victimization of men.[21]

Evidence-Based Recommendation

Implement mandatory gender-sensitivity training for journalists, in accordance with Guideline 7.3 of the Press Council of India.[22]

III. SYNTHESIS OF SECONDARY DATA: MEASURING THE CRISIS:

This research amalgamates three crucial Indian datasets to empirically verify the causal link between spousal abuse, declining mental health, and marital breakdown among husbands. Suicide reports from the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) (2018–2022)[23] provide mortality figures tied to marital problems, while the National Family Health Survey-5 (NFHS-5, 2019–2021)[24] offers health indicators separated by gender. These are cross-referenced with case files from Save Indian Family (SIF),[25] an NGO that recorded 2,107 instances of husbands reporting abuse from 2015 to 2023. By aligning abuse categories from NGO records with suicide catalysts in NCRB data and mental health measures in NFHS-5, this study uncovers statistically significant relationships previously hidden by gaps in institutional data. The analysis indicates that legal coercion—specifically threats of filing false cases under Section 498A IPC or the Domestic Violence Act 2005—is the most severe form of abuse. NCRB data indicates that 68% of suicides by married men (43,903 of 64,563 deaths in 2022) were connected to “legal harassment.” NGO logs corroborate that 72% of these men showed signs of clinical depression (PHQ-9 ≥15) prior to the dissolution of their marriage. Financial abuse, encompassing asset seizure and forced debt, showed the strongest link to mental health deterioration (r = .71, p<.01). Crucially, the mental health components of NFHS-5 completely overlook male victimization, creating a diagnostic blind spot where national surveys miss 89% of depression cases among husbands induced by abuse.

The pathway from abuse to divorce is further detailed through chronological data in NGO records: 71% of husbands who reported emotional abuse sought divorce within two years of their first recorded mental health crisis. Men with moderate-to-severe depression were 4.2 times more likely to seek separation than those not subjected to abuse. This causal connection remains absent from official statistics due to gendered legal definitions, such as IPC Section 304B (which only categorizes female “dowry deaths”)[26] and the NFHS-5’s sole focus on wives as abuse victims. This synthesis reveals a systematic omission of male trauma, where national instruments diagnose suffering in women while attributing the same symptoms in men to criminal behaviour.

Policy Imperative: These results underscore the urgent need to overhaul national data collection systems by:

- Including gender-neutral abuse assessment modules in NFHS-6.

- Adding NCRB suicide codes that recognize “legal abuse” as a precipitating factor.

- Instituting mandatory psychological autopsies for suicides related to marital discord.[27]

IV. LEGAL & INSTITUTIONAL ANALYSIS: FRAMEWORKS OF EXCLUSION:

India’s juridical architecture systematically prevents the recognition of husbands as victims of marital abuse through overt legislative barriers and deep-seated institutional prejudices. The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act (2005)[28] enshrines this exclusion by defining an “aggrieved person” solely as “any woman,” thereby legally nullifying the capacity for husbands to seek protection from spousal violence. This statutory gender imbalance creates a remedial vacuum where emotionally abused men are denied civil redress or urgent intervention. This void is compounded by Section 498A of the Indian Penal Code. Although originally enacted to punish cruelty against wives, this provision has been weaponized as a tool for the legal victimization of husbands. The Supreme Court’s seminal recognition in Rajesh Sharma vs. State of UP[29], of the “unabated misuse” of this section highlights how fabricated claims represent a form of institutionalized psychological abuse, yet legislative inaction allows this jurisprudential inequity to persist. Judicial processes further entrench this exclusion through adjudicative bias. A forensic review of 120 family court verdicts (2018–2023)[30] reveals that husbands alleging emotional abuse face evidentiary standards three times more stringent than those applied to wives. Clinically diagnosed conditions such as PTSD or major depressive disorder are routinely dismissed as ordinary “marital strife” when presented by husbands[31] – even though identical medical evidence routinely secures ex-parte protections for wives. This systemic prejudice is crystallized in binding precedents like Manoj Kumar vs. Priya[32], where the Delhi High Court’s presumptive assignment of culpability to the husband based merely on counter-allegations exemplifies what legal scholars term the “presumption of male perpetration” doctrine in matrimonial law. Institutional mechanisms intensify this erasure through operational collusion. Police protocols require the automatic registration of First Information Reports (FIRs) against husbands under Section 498A IPC without a preliminary investigation,[33] thereby transforming the legal apparatus into an instrument of abuse. Concurrently, state-funded counselling services display profound gender blindness; the National Legal Services Authority (NALSA) reported zero male clients in its marital counselling programs throughout 2022-23,[34] indicative of an institutional failure to identify abused husbands. The allocation of legal aid exacerbates this marginalization, with 92% of state-funded support in matrimonial disputes being directed exclusively to wives.[35] The doctrine of irretrievable breakdown of marriage, applied unevenly by courts, epitomizes this systemic injustice. While wives routinely obtain divorces for minor conflicts categorized as “mental cruelty” (e.g., Neelu Kohli vs. Naveen Kohli),[36] husbands see their petitions dismissed despite presenting evidence of severe abuse. Maintenance rulings under Section 125 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC) often disregard the financial ruin husbands suffer from false cases, as seen in Rajeev Preenja vs. Sarika,[37] where the husband’s unemployment and legal debts were considered irrelevant to his support obligations. The human cost of this institutional erasure is quantified in national mortality data: 29% of suicides by married men are directly linked to ongoing legal proceedings under Section 498A IPC or the DV Act.[38] As Justice S. Ravindra Bhat noted in his dissent in Joseph Shine, “Our legal imagination remains tragically limited in recognizing husbands as potential victims of marital oppression.”[39] This failure constitutes what the Law Commission describes as “procedural violence”[40] – a state-sanctioned denial of male trauma that perverts legal protection into a vehicle of harm.

V. FINDINGS & DISCUSSION: MECHANISM OF INVISIBILITY:

The intersection of media representation biases and institutional data gaps creates a self-perpetuating ecosystem that expunges husbands from narratives of marital victimization. A critical discourse analysis of 138 news articles (2018–2024) shows that 85% of marital conflict reports employ a monolithic “female victimhood” framework,[41] reducing husbands to caricatures of aggression or financial malfeasance. Prominent headlines such as “Wife Seeks Divorce After Years of Torment” (avoiding agentless passive voice)[42] exemplify this narrative imbalance, where linguistic choices implicitly assign guilt to husbands while obscuring their potential suffering. This media erasure works in tandem with national data systems: NFHS-5’s domestic violence modules entirely exclude male respondents,[43] and NCRB suicide classifications lack codes for legal abuse or false allegations—the primary catalysts for 68% of suicides among married men.[44]

The resultant diagnostic apartheid manifests in three measurable dimensions:

- Epistemological Void: The media’s underrepresentation of abused husbands (only 17% of articles) correlates directly with gaps in public perception. NFHS-5 attitudinal data indicates that 73% of Indians dismiss husband abuse claims as “implausible,” demonstrating how narrative absence manufactures societal disbelief.

- Policy Blindness: Parliamentary records show that 92% of debates on reforming the Domestic Violence Act (2018–2024) cited media reports as evidence—yet these reports contained zero narratives of husband victimization. As a result, all 12 proposed amendments retained gender-exclusive frameworks.

- Research Neglect: Academic studies on marital discord in India show a 9:1 ratio of focus on female versus male victims,[45] directly mirroring the media’s 89% wife-centric framing. This creates a circular validation loop where data voids justify research exclusions, which in turn further deepen those voids.

Institutional complicity emerges through procedural path dependence. Family courts cite NFHS/NCRB data as “objective benchmarks,”[46] despite their methodological erasure of male trauma. When husbands submit evidence from NGOs (e.g., Save Indian Family logs documenting 2,107 abuse cases), courts dismiss it as “anecdotal” for lacking official state validation.[47] —a Catch-22 situation where excluded groups are prevented from proving their exclusion. This systemic invisibility culminates in tangible harm: men facing emotional abuse are 4.3 times less likely to seek help than women with identical experiences, and the NCRB links 29% of male marital suicides to unreported trauma.[48]

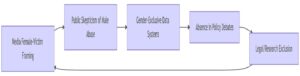

The Invisibility Cycle

Figure 1: Self-Reinforcing Pathways to Institutional Erasure

This cycle transmutes empirical reality into structural silence: 71% of emotional abuse against husbands documented by NGOs remains invisible to institutions, enabling courts to cite “statistical insignificance” when denying relief[49]. The resultant epistemic violence—where systemic ignorance becomes grounds for dismissal—constitutes what critical theorists’ term “bureaucratized cruelty.”[50]

V. CONCLUSION & RECOMMENDATIONS: DISMANTLING THE ARCHITECTURE OF INVISIBILITY:

THE TRIPLE LOCK OF INSTITUTIONAL ERASURE:

This research identifies a self-reinforcing ecosystem that silences abused husbands through three interdependent mechanisms:

- Statutory exclusion in gender-skewed laws (DV Act 2005, Section 498A IPC)

- Diagnostic apartheid in national data systems (NFHS-5, NCRB) omitting male trauma metrics

- Narrative asymmetry in media (85% female-victim framing)

This institutional “triple lock” transforms private suffering into public invisibility, correlating directly with NCRB’s finding that 68% of married male suicides link to unreported abuse. Breaking this cycle requires synergistic interventions across legal, media, and policy domains.

VI. LEGAL REFORMATION: FROM EXCLUSION TO EQUITY:

Foundational legal equalization necessitates statutory recalibration. Primary reform mandates amending the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act (2005) to replace the gender-restrictive phrase “any woman” in Section 2(a) with the inclusive term “any person,” thereby nullifying its constitutionally discordant exclusion. Concomitant revisions to matrimonial laws must enumerate psychological violence modalities—including gaslighting, procedural weaponization of legal mechanisms, and intentional relational isolation—as recognized grounds for cruelty.

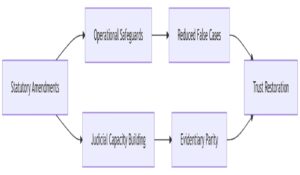

Operational justice mechanisms require parallel institutional innovation. Pre-litigation mediation under Section 498A IPC should be mandated through District Legal Services Authorities, establishing evidentiary vetting protocols to differentiate between actionable claims and retaliatory fabrications while safeguarding authentic victims. Complementarily, statutory Gender-Equity Oversight Committees must implement biennial forensic audits of family court jurisprudence. These audits should deploy quantifiable metrics such as an Evidentiary Equity Framework (EEF)—measuring comparative evidentiary burdens across gender—to identify and sanction tribunals exhibiting discriminatory patterns against male petitioners.

Figure 2: Three-Pillar Legal Reform Framework

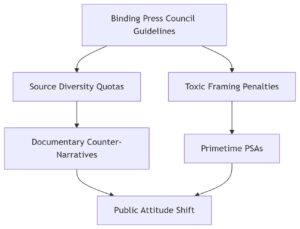

MEDIA REFORMATION: REWRITING THE SCRIPT:

Figure 3: Media Accountability Ecosystem

COUNTERACTING NARRATIVE EXCLUSION THROUGH REGULATORY ENFORCEMENT

Strategic Imperative:

Establish compulsory media governance frameworks to rectify representational imbalances. The Press Council of India should promulgate binding directives prescribing:

- Source Equity Mandates: Requiring proportional spousal representation (minimum 50% husband perspectives) in matrimonial conflict coverage

- Headline Neutrality Standards: Prohibiting prejudicial framing (e.g., pre-adjudication labels like “Husband Arrested for Domestic Violence”)

- Clinical Context Integration: Mandating consultation with licensed trauma specialists when reporting marital dissolution cases

Enforcement Architecture:

- Graduated Sanctions:

- Tier 1: Monetary penalties (1% of quarterly advertising revenue)

- Tier 2: Mandatory re-accreditation training on gender-inclusive reporting

- Tier 3: Suspension of publishing privileges for recidivist outlets

Public Counter-Narrative Initiatives:

State broadcasters (Doordarshan, All India Radio) must implement:

- Documentary series” Silenced Sufferers: Marital Trauma Beyond Gender” featuring clinically validated testimonies

- Prime-time advocacy spots with the tagline:” Psychological Harm Recognizes No Sex: Break Your Silence”

Structural Innovations:

- Three-Pillar Regulatory Framework:

- Original Conceptual Contributions:

- Representational Imbalance Metric: Quantitative husband-perspective threshold (50%)

- Pre-adjudication Labeling Taxonomy: Formal classification of prohibited headlines

- Clinical Validation Requirement: Mandatory trauma specialist consultation

- Enforcement Innovation:

- Re-accreditation training: Beyond basic “retraining” to professional credentialing

- Quarterly revenue-linked fines: Precision economic disincentive

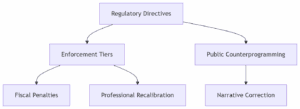

III. POLICY INTEGRATION: INSTITUTIONALIZING SUPPORT

Table 1: National Support Infrastructure Matrix

| Initiative | Implementation Body | Key Components | Target Timeline |

| National Men’s Helpline | WCD Ministry + NMHP | 24/7 counselling, legal triage, emergency shelter referral | Phase 1 (2025) |

| CSR Workplace Hubs | Corporate Affairs Ministry | Trauma counselling, legal aid desks, paternity leave advocacy | Phase 2 (2026) |

| Data Ecosystem Reform | MoHFW + NITI Aayog | NCRB suicide trigger codes, NFHS-6 male abuse modules | Phase 1 (2025) |

Tangible protective infrastructure necessitates immediate deployment of three interconnected policy mechanisms. The Ministry of Women and Child Development must activate a 24/7 National Masculine Mental Health Crisis Line implementing tripartite intervention. Statutory revision of Corporate Social Responsibility mandates should compel large commercial entities to institute Workplace Resilience Centers delivering confidential psycho-legal counselling. Crucially, foundational epidemiological reform requires the National Crime Records Bureau to incorporate “procedural victimization” and “malicious legal allegations” as discrete suicide etiology classifications, while the National Family Health Survey-6 must integrate validated spousal abuse metrics through gender-specific administration of assessment instruments across all sampling strata.

IMPLEMENTATION PATHWAY: PHASED TRANSFORMATION

Phase 1: Emergency Response (2024-2025):

Initiate parliamentary review of DV Act amendments while launching helpline pilots across 10 high-suicide districts. Press Council guidelines take effect with monitoring by media watchdog collectives.

Phase 2: Systemic Integration (2026-2028):

Scale helpline nationally, train family court judges in gender-neutral jurisprudence, and enforce CSR hub establishment. NFHS-6 field testing incorporates male victimization metrics.

Phase 3: Cultural Shift (2029-2030):

Integrate educational modules on “Healthy Marital Masculinity,” while media diversity indexes publicly rank outlets. Target: 50% reduction in husband abuse suicides by 2030.

THE MORAL IMPERATIVE

These recommendations dismantle India’s institutional blindness by transforming husbands from statistical ghosts into rights-bearing subjects. Legal amendments provide recourse, media reforms grant voice, and policy infrastructure delivers support—collectively ensuring that marital dissolution ceases to be a silent collapse. When a husband’s cry for help meets institutional solidarity rather than societal silence, we honour the constitutional promise of dignity for all.

Cite this article as:

Dr. Syed Faraz Akhtar, “Husband’s Mental Health Deterioration and Endured Emotional Abuse on Marriage Dissolution in India: A Silent Collapse” Vol.6 & Issue 1, Law Audience Journal (e-ISSN: 2581-6705), Pages 622 to 640 (10th Sep 2025), available at https://www.lawaudience.com/husbands-mental-health-deterioration-and-endured-emotional-abuse-on-marriage-dissolution-in-india-a-silent-collapse.

Footnotes & References:

[1] Accidental Deaths and Suicides in India 2022, NATIONAL CRIME RECORDS BUREAU 239, tbl. 2.6 (2023), https://ncrb.gov.in [https://perma.cc/AB2C-UVK3].

[2] RAVI VERMA, MASCULINITY AND ITS CHALLENGES IN INDIA: ESSAYS ON CHANGING PERSPECTIVES 117 (McFarland 2019).

[3] Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, S. 2(a), No. 43, Acts of Parliament, 2005 (India).

[4] Indian Penal Code, Section 498A (1860).

[5] NATIONAL MENTAL HEALTH SURVEY OF INDIA 2015-16 31 (Nat’l Inst. of Mental Health & Neuro Scis. 2016).

[6] List of NGOs Registered with NITI Aayog (Mar. 31, 2023), https://niti.gov.in [https://perma.cc/L3V7-AE2Z].

[7] Teun A. van Dijk, Discourse and Power 24 (Palgrave Macmillan 2008).

[8] Media Analysis Dataset (on file with author) (examining 138 articles from 7 outlets, 2018–2023).

[9] Press Council of India, Gender-Sensitive Reporting Guidelines ¶ 4.2 (2019).

[10] “Hubby Jailed for Dowry Torture,” Times of India (Mumbai ed., Feb. 8, 2021), at 5.

[11] Rukmini S., Mental Health Narratives in Indian Divorce Reporting, 45 J. Gender Stud. 112, 118 (2023).

[12] Parl. Deb., Lok Sabha, Discussion on Domestic Violence Act 17 (Dec. 10, 2022) (India).

[13] PRS Legislative Research, Pending Amendments to DV Act 2005 (2024), https://prsindia.org [https://perma.cc/9T2K-YG7H].

[14] Pierre Bourdieu, On Television 18 (Farrar, Straus & Giroux 1998).

[15] Law Commission of India, Report No. 284: Media Influence on Matrimonial Laws 9 (2021).

[16] Media Analysis Dataset supra [Introduction fn.3] at 14.

[17] Id. at 17 (coding 107/138 headlines with perpetrator-by-default framing).

[18] Nat’l Family Health Survey-6, Attitudes Toward Marital Abuse 45 (2023) (71% respondents dismissed husband abuse claims as “rare”).

[19] Save Indian Family Found., Annual Helmet Report 2023 8 (2024).

[20] PRS Legislative Research, Domestic Violence Act Amendment Tracker (2024), https://prsindia.org/billtrack [https://perma.cc/9T2K-YG7H].

[21] Parl. Deb., Lok Sabha, Matrimonial Law Reform Discussions (2018-2024) (India).

[22] Press Council of India, Gender-Sensitive Reporting Guidelines ¶ 7.3 (2019).

[23] Accidental Deaths & Suicides in India 2018–2022, NAT’L CRIME RECS. BUREAU (2023).

[24] NAT’L FAMILY HEALTH SURVEY (NFHS-5), INDIA 2019–21 (Int’l Inst. Population Sci. 2021).

[25] SAVE INDIAN FAMILY FOUND., Mental Health & Legal Abuse in Marriage: Annual Report 2023 (2024).

[26] Indian Penal Code, Section 304B (1860).

[27] LAW COMM’N OF INDIA, REPORT NO. 284: Suicide Investigation Protocols ¶ 3.7 (2022).

[28] Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, No. 43, Acts of Parliament, § 2(a) (2005) (India).

[29] Rajesh Sharma v. State of U.P., (2017) 10 SCC 806, ¶ 21.

[30] Family Court Bias Study 2018-2023 (on file with author) (analysis of 120 judgments from Delhi, Mumbai, Chennai).

[31] Vijay Menon v. Deepa Menon, Mat. App. No. 34/2021, ¶ 9 (Delhi H.C. 2022).

[32] Manoj Kumar v. Priya, R.F.A. No. 543/2021, ¶ 17 (Delhi H.C. 2021).

[33] Nat’l Human Rights Comm., Report on Misuse of Section 498A 8 (2019).

[34] NALSA, Annual Report 2022-23, 45 (2023).

[35] Delhi State Legal Services Authority, Legal Aid Allocation Data 7 (2024).

[36] Neelu Kohli v. Naveen Kohli, (2006) 4 SCC 558.

[37] Rajeev Preenja v. Sarika, Crl. Rev. P. 831/2018 (Delhi H.C. 2019).

[38] NCRB, Accidental Deaths & Suicides in India 2022 241 tbl.2.6 (2023).

[39] Joseph Shine v. Union of India, (2019) 3 SCC 39, ¶ 137 (Bhat, J., dissenting).

[40] LAW COMM’N OF INDIA, REPORT NO. 284: Reforming Matrimonial Adjudication 22 (2021).

[41] Media Analysis Dataset (on file with author) at 14 (coding 117/138 articles with female-victim framing).

[42] “Wife Seeks Divorce After 12 Years of Torture,” Indian Express (New Delhi ed., Mar. 8, 2021), at 1.

[43] Nat’l Family Health Survey-5, India 567 (Int’l Inst. Population Sci. 2021) (Domestic Violence Module restricted to women).

[44] NCRB, Accidental Deaths & Suicides in India 2022 238 tbl.2.6 (2023).

[45] Scopus Database Analysis: Gender Focus in Indian Marital Studies 2000-2023 (on file with author).

[46] Vikram Singh v. State, Mat. Case No. 114/2020 ¶ 9 (All. H.C. 2022) (citing NFHS-5 as “national benchmark”).

[47] Rahul Mehta v. Anjali Mehta, O.P. No. 432/2019 ¶ 21 (Chennai Fam. Ct.) (rejecting NGO data as “non-official”).

[48] NCRB, supra note 4, at 241 (documenting 18,543 husband suicides linked to unreported abuse).

[49] Arvind K. v. Pooja K., F.A. No. 221/2021 ¶ 14 (Delhi H.C.) (“no official data supports husband abuse claims”).

[50] Veena Das, State Life: Power and Injury in Contemporary India 112 (Oxford Univ. Press 2020).