Click here to download the full paper (PDF)

Authored By: Ms. Sana Khan, Research Scholar, Department of Law, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh (U.P.), India,

Click here for Copyright Policy.

ABSTRACT:

While motherhood fulfills a woman, it is not feasible for every woman to experience it naturally. Infertility is a global health issue that has persisted throughout history. The growth of science and technology has provided treatments for infertility, particularly with the creation of In Vitro Fertilization (IVF), enabling individuals to conceive their own children. With the rapid growth of Assisted Reproductive Technologies or ARTs, surrogacy has become a crucial solution for individuals and couples battling infertility or other impediments to natural conception. The three principal legislations in India that govern an individual’s reproductive choices regarding abortion and the adoption of Assisted Reproductive Technologies (ARTs) have been examined. As surrogacy practices advance, comprehending the legal and ethical ramifications of surrogacy contracts becomes increasingly essential. This paper examines India’s surrogacy laws, with a particular emphasis on the Surrogacy (Regulation) Act of 2021, which represents a major change by outlawing commercial surrogacy and supporting altruistic arrangements. The piece of writing assesses the Act’s closure of prior regulatory gaps and examines the enforceability of surrogacy agreement under the Indian Contract Act of 1872. The legal, moral, and societal ramifications of an abortion clause in a surrogacy contract are examined. How can surrogate autonomy and agency are impacted by abortion clauses in surrogacy contracts.

Keywords: Surrogacy Regulation, Legal enforceability, ART’s, Abortion clause, Surrogacy Contract.

I. INTRODUCTION:

Contemporary Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART) has revolutionized the traditional concept of maternity. Surrogacy is a significant reproductive intervention that enables female with uterine anomalies, severe health conditions, and other pregnancy-related risks for achieving maternity by the implantation of autologous or donor-derived embryos into the uterus of a gestational carrier. Likewise, this approach enables homosexual couples and individuals to attain fatherhood by the implantation of embryos created from autologous sperm and donor oocytes in a surrogate. Traditional and gestational surrogacy are two unique scenarios that may be characterized by the characteristics of the embryo and the fertilization techniques employed. In the conventional method, the surrogate mother undergoes in vitro fertilization using the sperm of the intended father and subsequently relinquishes an infant to the selected parental pair after birth. In the gestational method, the surrogate mother is not genetically linked to the kid, as the embryo originates from a mix of gametes that do not belong to the gestational carrier. Both conventional and gestational surrogacy includes the surrogate undergoing pregnancy and childbirth, following which the infant is entrusted to the intended parents for lifelong upbringing. The extensive array of reproductive options has increasingly intensified issues of ethics, law, and society, compelling legal regimes to amend current laws to align with citizens’ expectations. This tendency reflects the changing perspectives of bioethical issues. Due to unresolved issues about the rights of all parties involved, nations permitting surrogacy continue to regard it as a legislative challenge.[1]

I.II MEANING OF SURROGACY:

The term “surrogate” derives from the Latin term “subrogate” meaning “to substitute.“[2] According to section 2(1)(zd) of Surrogacy (Regulation) Act 2021 surrogacy means “a practice whereby one women bears and gives birth to a child for an intended couple with the intention of handing over such child to the intended couple after the birth.”[3] A surrogate mother is a female who gestates and delivers an infant with the intention of relinquishing parental rights to a different person or couple, referred to as the commissioning or intended parents. Surrogacy has emerged as a significant reproductive intervention, particularly for women unable to sustain pregnancies owing to medical issues or uterine abnormalities. IVF technology enables women to attain parenthood by creating embryos using their own or donor eggs, which are then transferred to a surrogate’s uterus. Moreover, surrogacy has enabled fatherhood for same-sex couples and single men by employing their sperm and donor eggs to create embryos.[4]

I.III TECHNOLOGY’S ROLE IN SURROGACY:

The human reproductive system exemplifies remarkable biological engineering. Through a series of intricate physiological and chemical processes, a sperm fertilizes an egg. These gametes, each with half the genetic information (DNA) from the parent, fuse to create a single cell called a zygote. Under normal circumstances, the zygote develops into a fetus over time, eventually being born as a child around nine months later.[5] The core components of this system are the sperm cells, egg cells, and the act of sexual intercourse between males and females. Whereas the egg cell contains a sizable nucleus encircled by cytoplasm that contains biological components, the sperm contains its genetic material in a nucleus rich in DNA. When fertilization occurs, the resulting zygote possesses every single chromosome, half from each parent. This child inherits its DNA from both parents, carrying on the genetic code for future generations. Unfortunately, not everyone can conceive naturally due to various factors causing infertility in one or both partners. Fortunately, modern science provides solutions through assisted reproductive technologies (ART). A variety of fundamental and sophisticated techniques are included in ART, which is intended to assist infertile couples in starting families.[6]

II. THE SURROGACY (REGULATION) ACT 2021:

Until 2021, Indian law did not explicitly address surrogacy. Only two legislative measures benefited parents seeking to utilize surrogacy: the Surrogacy (Regulation) Bill and the Bill to Regulate Assisted Reproductive Technology. The Indian Parliament had been considering legislation for an extended period. The proposals are ultimately revised to align with contemporary Indian needs and are enacted as laws, namely the Assisted Reproductive Technology (Regulation) Act of 2021 and the Surrogacy (Regulation) Act of 2021. The Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act of 1971 and the Pre-Conception and Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques (Prohibition of Sex Selection) Act of 1994 are two instances of indirect legislation available to protect women’s reproductive rights. In actuality, these policies fail to address problem pertaining to the rights of surrogate mother, an exploitation of female through commercial surrogacy, and the causes and consequences of violating a surrogacy contract. In this context, India has gained advantages from the implementation of two new direct legislations. Nonetheless, the new regulations are also facing criticism in an effort to enhance future prospects.[7]

II.I FEATURES OF THE ACT:

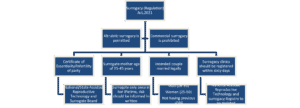

The Surrogacy (Regulation) Act, 2021 grants distinct rights and safeguards to both the surrogate and the infant conceived via surrogacy. Under the Act, several regulations and certify bodies for surrogacy and surrogacy therapies are also formed.

PROHIBITION AND REGULATION OF SURROGACY CLINICS:

The Act stipulates that no surrogacy clinic is permitted to engage in, collaborate with, or facilitate activities pertaining to surrogacy and surrogacy treatment unless it is duly registered pursuant to the Act.[8] Any individual or entity, including surrogacy clinics, pediatricians, gynecologists, embryologists, registered medical practitioners, or others, is prohibited from participating when it comes to commercial surrogacy or the promotion, publication, canvassing, propagation, or advertising of any content that suggests a female to serve as a surrogate mother.[9] The statute forbids the execution or facilitation of an abortion during a surrogacy unless there is explicit approval from the surrogate mother and a licensed medical practitioner, including gynecologists, pediatricians, embryologists, intended parents, and others.[10] This law explicitly prohibits commercial surrogacy, the marketing of surrogate motherhood, and surrogate motherhood techniques. It pertains to surrogacy clinics and any other venues where such operations may occur.[11] The Act mandates that surrogacy shall not proceed until the prospective couple obtains a certificate of essentiality. The certificate must be issued by the relevant authority and validated by the supervisor of the surrogacy clinic. Furthermore, to ascertain the infertility status of one or both prospective parents, they must provide the District Medical Board’s infertility certificate. The Act mandates that the surrogate mother must obtain insurance for complications arising post-delivery, extending for a duration of sixteen months and it must be obtained from an insurance company or agency fully authorized by the Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority of India.[12]

SURROGACY CLINIC REGISTRATION:

The Act mandates that a surrogacy clinic must finalize the registration procedure prior to providing surrogacy services.[13] The Act mandates that the registration application must be filed within 60 days from the date of the competent body’s appointment as specified in the Act.[14] The Act prohibits the surrogacy center from proceeding with any surrogacy procedures until registration is completed within sixty days following the appointment of the authorized authority. Moreover, it is specified that this registration will be valid for a maximum of three years, after which the clinic must reinitiate the registration procedure.[15]

FORMATION OF NATIONAL AND STATE SURROGACY BOARDS AND OTHER AGENCIES PURSUANT TO THE ACT:

The Act mandates the creation of surrogacy boards at both national and state levels, with the state boards being particularly extensive.[16] The legislation establishes the National Assisted Reproductive Technology and Surrogacy Registry, which serves to register surrogacy clinics, among other objectives.[17]

ELIGIBILITY CRITERIA FOR SURROGATE:

According to the legislation, a surrogate is required to be a married woman who has at least one biological child, and her age must fall between 25 and 35 years at the time of implantation. It further delineates that she must be a direct relative of the individuals embarking on the union of marriage. Furthermore, it is advisable that she refrains from donating her gametes and from acting as a surrogate mother more than once during her lifetime. It further mandates that surrogates obtain an official document of the state of both bodily and mental well-being for surrogacy and associated therapies provided by a licensed healthcare professional prior to initiating the practice.[18]

ELIGIBILITY CRITERIA FOR INTENDING COUPLE:

The eligibility conditions for the prospective couple dictate that the female must be aged between twenty-three and fifty years, while the male must be aged between twenty-six and fifty-five years on the day of certification.[19] In case of Rajitha P V vs. Union of India[20], the Kerala High Court has ruled that an intended women is eligible for surrogacy throughout the age of 50 years, and her eligibility ceases only when the intended women turns 51. The Division Bench of CJ Nitin Jamdar and Justice S. Manu thus reversed the decision of single bench in Rajitha P V vs. Union of India (2025), which held that intending women would be eligible for surrogacy when she attains the age of 23 and ceases to be eligible on the preceding day of her 50th birthday. In reaching its conclusion, the division bench interpreted s.4(c)(i) of the Surrogacy (Regulation) Act, 2021 which stipulates that the intended couple must be between the age of 23 to 50 years old for females and between 26 to 55 years old males on the day of certification to obtain eligibility certificate for surrogacy. The court also relied on Section 9 of the General Clauses Act, 1897, emphasizing the significance of the word ‘to’ in the prescribed age range to support its interpretation. Moreover, it specifies that the intended couples must have gotten married for a minimum of 5 years, hold Indian citizenship and not have any living children regardless of whether they are biological, adopted, or born through surrogacy. Parents of children with mental and physical disabilities, those afflicted by life-threatening disorders, or individuals diagnosed with terminal illnesses lacking a cure may pursue validation from relevant authorities. The Act provides that divorced and widowed women aged thirty-five to forty-five may serve as sole commissioning parents for their children.

SURROGATE’S RIGHT TO WITHDRAW CONSENT:

According to the Act’s provision, no individual may initiate or perform surrogacy procedures without first informing the surrogate mother of all recognized adverse effects and aftereffects and obtaining her explicit written permission. The Act mandates that a surrogate mother can retain the right to rescind her consent to surrogacy prior to the implantation of the embryo in her uterus.[21] The Act stipulates that no individual, organization, surrogacy clinic, laboratory, or clinical institution may compel a surrogate mother into terminating a pregnancy at any stage of the surrogacy process, save as permitted by law.[22]

RESTRICTIONS ON THE ABANDONMENT OF A CHILD CONCEIVED THROUGH SURROGACY:

The Act forbids the abandonment of a child conceived via surrogacy for any reason, including genetic defects, birth defects, other medical conditions, subsequent development of defects, the child’s gender, or the conception of multiple children by intended parents, regardless of location, whether in India or abroad. Furthermore, it stipulates that the infant must be regarded as the biological offspring of the intended spouse and shall be entitled to all rights and advantages conferred by applicable law to a natural child.

BAN ON COMMERCIAL SURROGACY, EXPLOITATION OF SURROGATE MOTHERS, AND OFFSPRING CONCEIVED VIA SURROGACY:

The Act forbids any private person, group, surrogacy center, lab, or clinical establishment from participating in or offering commercial surrogacy, operating a racket or organized group to recruit or select surrogate mothers. The legislation also prohibits the printing, distribution, and transmission of advertisements pertaining to commercial surrogacy. It is unacceptable for any organization to do any of the following: abandon, disown, or exploit surrogate children, or to enable any of these things to happen to surrogate children. Moreover, the exploitation of surrogates is prohibited by law. The Act forbids authorities from selling human embryos or gametes for surrogacy and from running any agency, scheme, or organization that engages in the sale, purchase, or trade of human embryos or gametes for surrogacy purposes.[23]

OFFENCES AND PENALTIES UNDER THE ACT:

The Act prohibits any individual, company, surrogacy clinic, laboratory, or healthcare institution from participating in commercial surrogacy activities. Furthermore, the Act prohibits clinics or enterprises from seeking surrogate mothers, using individual brokers or middlemen to facilitate surrogacy arrangements, or conducting surrogacy treatments unless they are associated with a certified surrogacy organization.[24] All of these circumstances are subject to imprisonment for a maximum of 10 years, in addition to a fine that may reach up to ten lakh rupees, pursuant to the Act. The Act has classified certain offenses as cognizable, non-bailable, and non-compoundable.[25]

II.II THE SURROGACY REGULATION RULES OF 2022:

The Union Government promulgated the Surrogacy Regulation Rules, 2022, delineating the prerequisites and directives applicable to registered surrogacy centers. These centers must maintain minimal number of employees’ composition that includes at least one gynecologist, anesthetist, embryologist, and counselor. Supplementary staff may be recruited from ART Level 2 clinics. The gynecologist must possess extensive expertise in performing ART procedures and hold a postgraduate degree in obstetrics and gynecology. Surrogacy clinics are required to register with the relevant government and remit the specified fees. Upon approval, a certificate of registration is issued and must be publicly shown inside the clinic premises. In cases of application rejection, cancellation, or suspension, the applicant is entitled to appeal within a 30-day period utilizing the specified appeal form. If the stored gametes or embryos are not endangered, authorized bodies can conduct unannounced inspections of surrogacy clinics, including their facilities, equipment, and documents. The surrogate mother’s informed consent, as specified in the rules, is needed for the surrogacy process. No more than three surrogacy attempts will be entertained. In general, the gynecologist is expected to implant a single embryo; but, in rare circumstances, the implantation of up to three embryos may be permitted. The protocols outlined in the MTP, Act 1971, must be adhered to if the surrogate mother chooses to end the pregnancy. Furthermore, it is obligatory for the prospective couple or woman to obtain health insurance that encompasses a period of thirty-six months for the surrogate mother’s safeguarding.[26]

II.III RECENT MODIFICATIONS AND PROGRESS:

The initial change to the Rules, communicated on 10 October 2022, altered Rule 5(2) pertaining to insurance coverage for surrogacy. The revised regulation mandates that the intended couple procure 36-month insurance and execute an affidavit affirming the coverage. The affidavit was formerly required to be sworn before the Metropolitan or First-Class Judicial Magistrate. This process became more flexible with the 2022 Amendment, which allowed the affidavit to be sworn before either a Notary Public or an Executive Magistrate. This modification is anticipated to optimize the procedure and facilitate the application process for prospective couples seeking surrogacy. The modification broadens the roster of authorized officials permitted to administer the affidavit, so offering the prospective couple other alternatives to fulfill the insurance coverage obligation. This will likely yield a more expedited and seamless surrogacy application procedure. Announced in March 2023, the second amendment to the Rules forbids intended couples from utilizing donor gametes for surrogacy. Previously, the regulation said that surrogacy treatment might encompass the fertilization of a donor egg using the husband’s sperm, which some read as permitting the use of donor gametes. The 2023 Amendment substitutes this provision with a new clause that specifically forbids the utilization of donor gametes for both couples and single women (widows or divorcees). The amendment explicitly states that gametes may not be procured from surrogate mothers. Consequently, prospective parents with medical complications with their gametes who require donor gametes to conceive may encounter challenges in pursuing surrogacy in India. The amendment limits the pool of eligible individuals who may commission surrogacy, in addition to imposing additional limitations related to age, marital status, and medical criteria.[27] In case of Arun Muthuval vs. Union of India[28], the woman, referred to as ‘Mrs. ABC’ for the purpose of confidentiality, has been diagnosed with Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser (MRKH) syndrome. Medical Board documents indicate that she has nonexistent ovaries and an absence uterus; hence she is incapable of producing her own eggs/oocytes. The couple began the gestational surrogacy process through a donor. The utilization of donor gametes is currently forbidden due to a government notification that amended the legislation. It specified that the “intended couple” must utilize their own gametes for surrogacy.

The petition was submitted to the Supreme Court contesting the change as an infringement on women’s parental rights. Senior counsel Sanjay Jain, representing the petitioner, said that the revised Paragraph 1(d) of the Surrogacy Regulation Rules 2022, which prohibits the use of donor eggs, has rendered it unfeasible for his client and her spouse to pursue surrogacy for the purpose of attaining parenthood. He said that the 2023 amendment violated Sections 2(r) and 4 of the Surrogacy Regulation Act, 2021, which acknowledged circumstances in which a medical condition would necessitate a couple’s decision to pursue gestational surrogacy to achieve parenthood. The court concurred with Jain’s assertion that the legislation allowing gestational surrogacy was “women-centric.” The woman’s inability to conceive owing to a medical or congenital condition was the only reason for opting for a surrogate kid. This condition encompasses the absence of a uterus, recurrent pregnancy losses, multiple gestations, or a medical condition that precludes the ability to sustain a pregnancy to term or poses a threat to life. The amendment must not contravene Rule 14(a), which explicitly acknowledges the absence of a uterus or related conditions as a medical justification for gestational surrogacy.[29]

III. ASSISTED REPRODUCTIVE TECHNOLOGY:

The ART Act 2021 seeks to regulate and oversee ART clinics and ART banks, which collect, screen, and store gametes, while preventing misuse and ensuring the safe and ethical conduct of ART services. It establishes the subsequent provisions:

- A bank may acquire semen from males aged 21 to 55 and oocytes from females aged 23 to 35. A woman can provide eggs just once in her lifetime, with a maximum extraction of seven eggs permitted. A bank must not provide gametes from a single donor to several commissioning parties, which may include a married couple or a single woman seeking assistance.

- The clinics are required to administer ART services only to women aged 21 to 50 and to men aged 21 to 55.

- ART procedures may only be conducted with the written consent of the donor and commissioning parties. The commissioning parties must offer insurance coverage for any loss, injury, or death originating from the egg donor.

- The clinics must offer competent counseling to the commissioning couple and the donor with all implications, including the likelihood of treatment success, enabling them to make an educated decision that serves their best interests.

- Pre-implantation genetic testing is permitted solely for the screening of human embryos for known hereditary or genetic disorders. A clinic is prohibited from offering a couple or woman a kid of a predetermined sex.

- A kid conceived with assisted reproductive technology (ART) will be regarded as the biological offspring of the commissioning couple. A donor shall possess no parental rights to the kid. The Act prevents single males, unmarried couples, transgender individuals, and same-sex couples from accessing ART services.[30]

Preet Inder Singh vs. Ganga Ram Hospital[31]:

The Delhi High Court enabled posthumous assisted reproduction by granting a couple in their sixties access to the sperm sample of their deceased son. The parents of a 30-year-old man who died from cancer in 2020 filed a petition in the Delhi High Court after a hospital declined to release their son’s cryopreserved semen sample. Sperm banking is prevalent among cancer patients since cancer therapies like radiation and chemotherapy can impact sperm count and quality. The hospital denied the deceased’s parents access to the frozen sperm, citing the absence of rules for gamete release in the absence of a spouse as the rationale for requiring appropriate judicial orders before delivery. This prompted the petitioners, desiring to uphold the memory of their departed son and raise a grandson, to seek the court’s assistance. With their daughter’s backing, they stated their readiness to assume full responsibility for any kid conceived through surrogacy with the frozen semen sample.[32]

IV. PURPOSE AND IMPORTANCE OF EXAMINING SURROGACY CONTRACTS IN INDIA:

The regulation of surrogacy contracts is essential because of the intricate relationships and legal rights involving the surrogate mother, the intended parents, and the unborn child. Surrogacy agreements are special because they sit at the nexus of family law, bioethics, and business law. A thorough examination of these contracts, which are frequently fraught with emotional and legal complications, is necessary to guarantee equity and safeguard the rights of those who are most in need, especially surrogate mothers. A number of examples of exploitation and abuse have resulted from the surrogacy industry’s explosive rise in India, particularly involving economically disadvantaged women who are hired as surrogates. A considerable percentage of surrogates were bound by contracts that offered no protection and subjected them to dire situations. Furthermore, custody and parenting issues generated legal complexity, as courts often encountered cases where surrogacy agreements were ambiguous or poorly enforceable. These issues underscored the imperative of developing a systematic legal framework to govern surrogacy agreements.[33] The Surrogacy (Regulation) Act, 2021 seeks to address this concern by banning commercial surrogacy and allowing only altruistic surrogacy for Indian citizens. This change raises important questions regarding the enforcement of surrogacy agreement under the new legal framework and the extent to which surrogacy remains accessible to prospective parents, particularly those facing infertility challenges.[34]

IV.I SURROGACY CONTRACT:

The parties involved in a surrogacy agreement, the intended parent(s) and the surrogate mother—must comprehend their respective roles and responsibilities. This type of agreement may or may not be documented in writing. A contract is established when the terms of an agreement between parties are documented in writing. The objective of any contract is to guarantee compliance with the conditions mutually agreed upon by the parties involved in a transaction. Nonetheless, there is contention on whether the parties’ accord in a surrogacy arrangement constitutes a contract. Therefore, it is essential to determine the legal legitimacy of a surrogacy partnership. In this context, understanding the definition of a contract and its legal implications, both generally and within the Indian legal framework, is essential. A legitimate contract necessitates the voluntary and informed assent of both parties and must be documented in writing. A contract is established when an offer is presented, accepted, and legitimate consideration is exchanged. According to Sir Frederick Pollock, “Every legally enforceable agreement and obligation constitutes a contract.” Each contracting party acquires rights and obligations commensurate with the rights and obligations of the other parties. Although all parties may anticipate an advantage from the contract (or the agreement may be considered inequitable by the judiciary), this does not suggest that all parties would derive equal benefits. Contracts are generally enforceable regardless of their written form; nonetheless, a written contract safeguards all parties involved. The objective of contract law is to address situations when parties breach a contract by failing to uphold their commitments or are unable to fulfill them due to unforeseen circumstances. The Indian Contract Act of 1872 codifies the legal principles that regulate contracts in India. This Act defines a contract as “a legally enforceable agreement.” The reciprocal obligations of both parties constitute a contract. Consequently, both a proposal and acceptance are necessary to establish contractual responsibilities. The predominant method for contract formation involves one party extending a proposal, which is then accepted by the other side. A contract delineates the rights and obligations of the parties concerned. When one party to a contract default on a contractual commitment, the other party is entitled to initiate legal action. It is essential to note that in every surrogacy arrangement, the intended parents and the surrogate mother reach a mutual agreement or understanding. The surrogate mother accepted an offer from the intended parents. The agreements established between the intended parents and the surrogate may be classified as contracts under the Indian Contract Act of 1872. A surrogacy contract entails a woman (either single or married) entering into a private agreement with the biological or intended parents of her unborn child, wherein she consents to utilize assisted reproductive technology to conceive, gestate the pregnancy, deliver the child, and subsequently relinquish all parental rights to the offspring. A surrogacy contract is an arrangement among a couple intending to have a child, a woman willing to gestate that child for them, and, in certain instances, the surrogate’s spouse. Most infertility clinics need the surrogate and the intended parents to execute a contract. A surrogacy agreement is created to avert any conflicts between the intended parents and the surrogate mother. Conflicts may emerge regarding the identification of the biological parent, the allocation of parental rights post the child’s eighteenth birthday, custody arrangements, financial responsibility for the surrogate’s medical expenses, compensation for the surrogate, liability for any harm incurred by the surrogate, and accountability for any shortcomings in the surrogate’s obligations, among other issues. A conventional surrogacy agreement will preclude any ambiguity and provide unequivocal wording in the event of disagreement. Consequently, a legally enforceable contract or agreement between the surrogate mother and the intended parent(s) is normal practice in all surrogacy arrangements. Surrogacy contracts may be established between non-related parties or between close relatives. It may be motivated by financial incentives or by genuine altruism, such as love or affection. Surrogacy arrangements can be classified as either “commercial” or “non-commercial” (altruistic) based on the type of financial remuneration involved. In a commercial surrogacy agreement, the intended parents’ consent to provide cash compensation to the surrogate for her services. Financially compensated surrogacy agreements are an alternative designation for these contracts. A surrogate involved in a non-commercial or altruistic surrogacy relationship neither anticipates nor receives compensation. The surrogate and the intended parents may reach an agreement about the payment for the surrogate’s medical expenses. This form of arrangement is sometimes referred to as a “contract for uncompensated surrogacy”. Surrogates may be obligated by their contracts to do medical and psychological evaluations prior to embryo transfer. In certain instances, the surrogate’s contract may mandate that she abstains from alcohol, drug usage, or smoking during the whole of the pregnancy. Certain contracts may stipulate the necessity of an amniocentesis test, and if the findings indicate complications with the pregnancy, the parents may have the option to terminate the pregnancy in accordance with the provisions of the agreement. Most surrogacy agreements forbid the surrogate mother from terminating the pregnancy unless it is essential to safeguard her life. The intended parents will cover all medical and health expenditures of the surrogate in return for her bearing their kid.

IV.II OBJECT AND PURPOSE OF SURROGACY CONTRACTS:

Every surrogacy agreement safeguards the interests of all parties involved, including the intended parents, the surrogate, and the surrogate child. Surrogacy contracts clearly delineate the responsibilities and entitlements of each partner. The welfare of the surrogate kid must also be considered. Consequently, each surrogacy agreement may encompass the following objectives:

- To verify that the intending parents and surrogate mother have consented to assisted reproductive technology and a full-term pregnancy. Each surrogacy arrangement is founded on the parties’ want to procreate.

- Identify the parents of the surrogate kid. The prospective parents execute a surrogacy contract to conceive and rear a child. The surrogate and her spouse do not desire children. Anonymous sperm or egg donors do not desire parental responsibilities either. Surrogacy agreements can establish the child’s paternity and maternity. The intended parents often execute a contract to conceive a child and undertake parental responsibilities. Pre-birth statements assist in addressing prospective issues.

- The surrogate forfeits her parental rights and surrenders the kid to the intended parents’ post-birth. If she alters her decision post-birth and refuses to relinquish the child to the intended parents, the surrogacy agreement will be rendered void. Surrogacy contracts explicitly terminate the surrogate mother’s parental rights to facilitate the placement of the surrogate child with the intended parents.

- The surrogate mother is compensated for her services and medical expenses as stipulated in the surrogacy agreement. Commercial surrogacy agreements compensate surrogates for their time and medical costs. Altruistic surrogacy agreements encompass just medical expenses. Each surrogacy contract mandates oversight of the surrogate’s conduct during the pregnancy. This guarantees appropriate fetal development and prohibits the surrogate from engaging in any activities that may jeopardize the kid. Ultimately, each surrogacy agreement encompasses unforeseen issues. Due to the inherent hazards associated with every pregnancy, such ridiculous scenarios may occur. Consequently, intended parents are accountable for any surrogate injuries or congenital anomalies as stipulated in the surrogacy agreement. The surrogacy agreement addresses matters such as divorce, disputes, death, or refusal to accept the kid.

IV.III ENFORCEABILITY OF CONTRACTS:

One of the most contentious topics in recent history is the question of whether surrogacy contracts should be enforced. Critics of surrogacy argue that legalizing contracts will promote positive eugenics, exploit surrogates, and lead to the objectification of women and children. Supporters contend that women ought to possess the autonomy to negotiate the use of their bodies, and that making surrogacy contracts invalid would infringe upon this freedom. Contrary to the assertions of its detractors, rendering surrogacy contracts enforceable would not result in exploitation, slavery, the trafficking of infants, or the commodification of human life; instead, it would safeguard the rights and interests of the involved parties by enabling them to uphold their obligations. India’s legislative structure fails to regulate surrogacy contracts. In the absence of a special regulation, contracts of this sort are governed by the basic principles regulating commercial transactions, including the Indian Contract Act of 1872[35] which governs all agreements made in India. According to Section 10 of the Act, a contract is valid and enforceable if it meets certain criteria:

i) There must be free consent of all parties.

ii) The contract must have a lawful consideration and lawful object.

iii) The parties to the contract must be competent to enter into a legal agreement.

Due to the possibility of exploitation and improper influence, surrogacy contracts frequently fell short of these requirements, particularly when operating under the commercial model. There are questions regarding whether the surrogate moms’ consent was genuinely free and informed because many of them signed these contracts out of financial need. Furthermore, questions arose about whether commercial surrogacy itself constituted a lawful object, particularly in light of ethical concerns surrounding the commodification of reproduction.[36]

V. ABORTION WITHIN THE CONTEXT OF SURROGACY CONTRACT:

The issue of abortion laws has been contentious since the beginning of time. However, the tension between a woman’s autonomy in determining her reproductive choices and the state’s obligation to safeguard life, which encompasses the protection of the unborn, has perpetually remained. Prior to the enactment of the Medical Termination Act in 1971, stringent legal procedures were in place. A multitude of ladies had no alternative but to utilize inadequate facilities. These procedures were predominantly unsanitary and employed rudimentary abortion techniques.[37] Intentionally causing a miscarriage is illegal under Section 312 of the IPC if it is not done in good faith to save the woman’s life. The Shah Committee was established in this situation to look into the high incidence of maternal death and morbidity in the nation as a result of unsafe abortion practices. The Committee suggested liberalizing abortion laws that would help in reducing unsafe abortions and bring down maternal mortality rates in the country. It eventually led to the enactment of The Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act, 1971.[38] The Indian government legalized abortion with the enactment of the MTP Act. According to Section 3(2) of the Act, abortion is authorized for duration of up to 12 weeks of gestation. The termination of pregnancy is furthermore authorized from 12 to 20 weeks if at least two medical practitioners deem it to be in the best interest of the mother and child. The MTP Act allows abortion access under specific criteria, including the woman’s permission, gestational stage, and the mental and physical health of both the woman and the fetus. Nonetheless, the 1971 legislation forbade the termination of a pregnancy before to 20 weeks, while the Amendment Act of 2021 implemented more substantial alterations extended the permissible duration for abortion to 24 weeks in circumstances involving particular vulnerable populations, including survivors of rape, victims of incest, women with impairments, and minors. Another significant component was the incorporation of an unmarried woman’s right to abortion. The new rules also seek to achieve many sustainable development goals (SDGs), specifically aimed at lowering maternal mortality rates and enhancing access to sexual and reproductive health and rights. Furthermore, the amendments will enhance a woman’s autonomy, dignity, privacy, and equity about abortion and pregnancy termination.[39] Certain provision relating to abortion under The Surrogacy (Regulation) Act, 2021 are no certified medical professional, gynecologist, pediatrician, embryologist, surrogacy clinic, intended couple, or other individual may in any way carry out or induce to be carried out sex selection for surrogacy.[40] Whether in India or abroad, the intended couple or intending woman is not allowed to leave the child born through a surrogacy procedure for any reason, including but not limited to birth defects, genetic defects, any other medical condition, defects that develop later, the child’s sex, the conception of multiple babies, and the like.[41] No individual, organization, surrogacy clinic, laboratory, or clinical facility shall compel the surrogate mother to end the pregnancy at any point throughout the surrogacy process, save under terms that may be stipulated.[42]

The MTP (Amendment) Act 2021 has introduced several significant modifications, which encompass:

- Extending the gestational limit for abortion from 20 weeks to 24 weeks for designated categories, including survivors of rape, children, women with physical or mental impairments, and those in humanitarian, catastrophe, or emergency contexts.

- All pregnancies up to 20 weeks necessitate the approval of one physician, while those between 20 and 24 weeks for certain groups of women require the consent of two physicians.

- Women may now abort an undesired pregnancy resulting from contraceptive failure, irrespective of their marital status.

- Termination of pregnancy beyond 24 weeks of gestation may only be conducted by a four-member Medical Board constituted in each State under the Act, based on fetal abnormalities.

In a recent judgment by the Apex Court in “X versus Principal Secretary, Health and Family Welfare Department, Government of NCT of Delhi,”[43] the Court provided a more progressive interpretation of the Act’s provisions.

- The artificial difference between married and unmarried women is not constitutionally viable; so, unmarried women are also permitted to obtain an abortion for pregnancies resulting from consensual relationships within the 20 to 24-week span.

- Under the MTP Act, marital rape is classified as rape.

- Additional legal stipulations must not be enforced on women pursuing abortions in conformity with the law and approval from a husband or partner for the termination of pregnancy is not necessary; however, a guardian’s approval is required for minors.

- The State must guarantee the right to reproductive autonomy and dignity for all people.

The struggle of female reproductive and physical autonomy persists, despite the prevalent acknowledgment of their equality and bodily integrity. Considering that physicians possess the ultimate authority to determine the cessation of a pregnancy, women’s rights remain constrained. It also fails to consider the reproductive rights of transgender males and others with different gender identities who possess the ability for pregnancy. Access to non-judgmental and safe abortion services remains elusive for the majority of women, particularly in rural regions. This is due to their lack of awareness regarding legal alternatives or their inability to obtain dependable healthcare services.[44]

The first review of surrogacy contract provisions reveals that the regulation and implementation of surrogacy agreements pose considerable human rights concerns. This pertains to contractual provisions that require the surrogate mother to deliver the infant, as well as stipulations that allow the intended parents to impose specific dietary or lifestyle requirements during gestation, and most notably, to mandate the surrogate mother to minimize the number of fetuses or end the pregnancy, as illustrated by the notable Baby Gammy case involving an Australian couple who requested their Thai surrogate to abort one twin diagnosed with Down’s Syndrome. The intended parents, unable to persuade the surrogate to terminate the pregnancy, rejected the developmentally challenged twin after his birth and subsequently abandoned him. Requests for the enforcement of surrogacy contracts are currently regulated by the specific national legislation pertinent to each situation.[45]

V.I VOLUNTARY TERMINATION OF THE PREGNANCY:

The voluntary termination of pregnancy clause in a normal surrogacy agreement specifies the procedures that ensue if the surrogate independently ends the pregnancy without the approval of the intended parents, provided that the termination is not medically warranted for the surrogate’s health. The voluntary termination of a pregnancy by a surrogate is deemed a breach of contract in most standard surrogacy agreements. As the court cannot mandate a woman to persist with her pregnancy, particular performance is not a viable option in this context. The remedies accessible to intended parents are often confined to the reimbursement of fees and expenditures previously disbursed to the surrogate, as well as occasionally covering additional costs incurred by the intended parents, such as legal fees and court expenses. Finally, some surrogacy agreements include provisions detailing the course of action if the fetus is suspected to have a physical anomaly. The surrogate agrees to relinquish her right to an abortion. Thus, the surrogate relinquishes her right to decide on the possibility of an abortion and, according to the stipulations of this contract, grants the intended parents’ full authority to select whether the surrogate should undergo an abortion. Irrespective of the surrogate’s personal beliefs, if the intended parents demand that the surrogate undergo an abortion, she is contractually bound to comply with this request.

Recommended Medical Attention and Amniocentesis:

This portion of the agreement delineates the sorts of medical treatment the surrogate will get during her pregnancy. If the surrogate declines certain tests, an abortion due to fetal health will not be permissible. This provision provides the intended parents with an enhanced capacity to be informed of any issues with the surrogate or fetus.[46]

V.II WHO HOLDS RIGHT TO ABORT:

The rights to reproduce and to get an abortion are opposing interpretations of the right to life and personal liberty as articulated in Article 21 of the Constitution, even though they are not explicitly included in the text. They signify a woman’s autonomy in making decisions about her body; so, if Article 21 holds any significance for her, the choice to conceive or terminate a pregnancy should fundamentally reside with her. In contrast to the right to procreate, abortion signifies liberation from the constraints of involuntary pregnancy. The clash between these rights may occur in two scenarios. In the initial scenario, a surrogate may choose to terminate the pregnancy; however, the commissioning parents opt to assert their right to reproductive autonomy by initiating a lawsuit for specific execution of the contract. This situation necessitates an assessment of whether a court would issue an injunction against the surrogate, as the absence of her right to terminate a pregnancy constitutes battery and undue hardship through the physical imposition of compulsory pregnancy, thereby infringing upon her rights against exploitation. In the second scenario, the commissioning parents may consider terminating the pregnancy if they identify significant complications in the prenatal or postnatal health of the fetus, or for personal reasons. The surrogate may view the commissioning parents’ intention to terminate the pregnancy as a violation of the contract. However, when the surrogate opts against abortion, the challenge for the courts becomes whether it is equitable and appropriate to mandate an abortion on demand. If the court permits the surrogate to take the fetus to term, it may result in undesirable parenting for the commissioning parents, which is a similarly catastrophic outcome. Certain advocates of surrogacy contend that the surrogacy agreement was established with the surrogate’s voluntary consent. Others contend that the surrogate maintains a fiduciary relationship with the commissioning parents, and this obligation of trust and loyalty necessitates that the surrogate abstain from pursuing her own interests to the detriment of the beneficiaries. Considering this fiduciary relationship with the commissioning parent, it may seem appropriate to compel a surrogate to execute her obligations. To protect a future child, a court may use the concept of state interest and mandate that a surrogate abstains from terminating a pregnancy or even require that the intended parents acquiesce to the surrogate’s choice to carry the child to term. The enforcement of state interest merely limits the unrestricted use of the abortion right by the contracting parties and intrudes upon their personal decisions.

Can Abortion Rights be waived?

The theory of waiver posits that an individual, as his own best judgment, possesses autonomy to relinquish the exercise of his rights. Consent to a contract, which contradicts the exercise of her right to abort, may therefore result in an instant forfeiture of that right. Numerous obiter dicta from Indian courts indicate a robust presumption against the surrender of fundamental rights. In Muthiah vs. CIT[47], the Court determined that a citizen cannot relinquish any basic rights. These rights serve not just the person but also function as a public policy advantage for society at large. In Basheshar Nath vs. CIT,[48] it was determined that there can be no waiver of the basic right inherent in Article 14, nor of any other fundamental rights provided by Part III of the Constitution. A prerequisite for waiving a right by consent is that the individual must possess adequate understanding of the pertinent facts and probable consequences of the waiver.[49]

Cite this article as:

Ms. Sana Khan, “Evaluating the Effectiveness of the Surrogacy Regulation Act, 2021: A Critical Analysis of the Abortion Clause” Vol.6 & Issue 1, Law Audience Journal (e-ISSN: 2581-6705), Pages 513 to 537 (5th August 2025), available at https://www.lawaudience.com/evaluating-the-effectiveness-of-the-surrogacy-regulation-act-2021-a-critical-analysis-of-the-abortion-clause/.

Bibliography:

[1]Paola Frati, Raffaele La Russa, et.al., “Bioethical issues and legal frameworks of surrogacy: A global perspective about the right to health and dignity” 258 European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology 1(2021).

[2] Swapnil Tripathi and Praveen Bala, “Redefining Parenthood: Surrogacy Amid Legal and Technological Evolution” 13 Journal of Nehru Gram Bharati University 46 (2024).

[3] The Surrogacy Regulation Act, 2021 (Act 47 of 2021), s. 2(1)(zd).

[4] NH Patel, YD Jadeja, et.al., “Insight into different aspects of surrogacy practices” 11 Journal of Human Reproductive Sciences 212–218 (2018).

[5] Columbus N. Ogbujah, Stanley O. Amanze, et.al., “Surrogacy and parenting in a hyper technological world: Ethical considerations” 11 Journal of the Association of Philosophy Professionals of Nigeria (appon), Philosophy and Praxis 24 (2021).

[6] Ibid.

[7] Dr. Sangeeta Chatterjee, “Surrogacy (Regulation) Act, 2021 in India: Problems and Prospects” 2 Annual International Journal on Analysis of Contemporary Legal Affairs 59-60 (2022).

[8] Supra note 3, s.3(i).

[9] Id., s. 3(v).

[10]Id., s. 3(vi).

[11]Id., s. 4.

[12]Id., s. 4(iii).

[13]Id., s. 10.

[14]Id., s. 10(3).

[15]Id., s. 11.

[16]Id., s. 14.

[17]Id., s. 15.

[18] Id., s. 4(b).

[19] Paramjit S. Jaswal & Jasdeep Kaur, “Surrogate Motherhood in India: An Analysis of Surrogacy (Regulation) Act, 2021” IV Shimla Law Review 257 (2021).

[20] (2025) LiveLaw 105(Ker).

[21] Supra note 3, s.6.

[22] Id., s. 7.

[23] Id., s. 35.

[24] Id., s. 38.

[25] Id., s. 43.

[26] Kriti, “Methods of treatment revised vide surrogacy (regulation) amendment rules” SCC Blog (2023), available at: https://www.scconline.com/blog/post/2023/03/15/ministry-of-health-and-family-welfare-notified-surrogacy-regulation-amendment-rules-legal-research-legal-update-legal-news/ (last visited on 11 March 2025).

[27] Suryansh, “The Legality of Surrogacy in India: Everything You Need to Know” Khurana and Khurana Advocates and IP Attorneys (2023), available at https://www.khuranaandkhurana.com/2030/06/16/legality-of-surrogacy-in-india-everything-you-need-to-know/ (last visited on 22nd March, 2025).

[28] (2024) SCC OnLine SC 140.

[29] Krishnadas Rajagopal, “Supreme Court allows surrogacy, strikes down rule banning use of donor gametes”, The Hindu, 27th October, 2023, available at https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/sc-upholds-womans-right-to-be-a-parent-through-surrogacy/article67462361.ece (last visited on March 29, 2025).

[30] Chitranji Malhotra, “Assisted Reproductive technologies and rights-Indian response to emerging structure” 8 Vidhyayana- an International Multidisciplinary Peer –Reviewed E- Journal-ISSN 2454-8596 882-883 (2023).

[31] ( 2015) 1 DLT 106.

[32] Sohini Ghosh, “Why Delhi HC allowed a 60- year-old couple to access dead son’s sperm”, The Indian Express, October 13, 2024.

[33] Samantha Brown, “The Impact of the Surrogacy (Regulation) Act, 2021 on Indian Surrogacy Practices” 56 Law and Society Review 453-475 (2022).

[34]Prithvi Raj, “Regulating Surrogacy in India: Legal Frameworks, Ethical Considerations and Lessons from Global Practices”4 Nyaayshastra Law Review 3-5 (2023).

[35] Prithviraj; Navya Gupta, et.al., “Legality And Enforceability of Surrogacy Contract: Challenges to Face” 10 Journal of Survey in Fisheries Science 1492-1494 (2023).

[36] Patricia Graham, “Ethics and Commercial Surrogacy: A Review” 16 Bioethics Journal 89-107 (2019).

[37] “Surrogacy and Abortion Laws”, 4 Center of Policy and Research Governance 14, July 7, 2022, available at https://www.cprgindia.org/surrogacy-and-abortion-laws/ (last visited on 14th March, 2025).

[38] Supra note 30 at 879.

[39] Supra note 37 at 15.

[40] Supra note 3, s. 3(viii).

[41] Id., s. 7.

[42] Id., s. 10.

[43] 2022 SCC OnLine SC 1321.

[44] Supra note 30 at 879-880.

[45] Arianna Vettorel, “Surrogacy Contracts and International Human Rights Law” 47 DEP 62-63 (2021).

[46] Britney Kern, “You are obligated to terminate this pregnancy immediately: The Contractual obligations of surrogate to abort her pregnancy” 36 Women’s Rights Law Reporter 11 (2014).

[47] 1956 AIR 269.

[48] 1959 AIR 149.

[49] Shamba Dey, “Right to Abort in Surrogacy Contracts: An Enquiry” 50 Economic and Political Weekly 16-19 (2015).