Click here to download the full paper (PDF)

Authored By: Reassessing Caste-Based Reservation In India: Impacts, Challenges and The Path Forward, Authored By: Anmol Jasrotia (LL.B), & Co-Authored By 1: Sombir Gulia (LL.B) & Co-Authored By 2: Garima Deeksha Chandani (LL.B), University Institute of Legal Studies, Chandigarh University,

Click here for Copyright Policy.

ABSTRACT:

Caste-Based Reservation system in India been enshrined in the Constitution as a form of affirmative action, seeks to redress historical injustices faced by Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, and Other Backward Classes. While these policies have expanded access to education and employment for marginalized groups, their effectiveness remains contested. This paper critically evaluates the socio-economic impact of reservations, highlighting persistent disparities such as the “creamy layer” phenomenon, where benefits disproportionately accrue to relatively privileged subgroups within reserved categories. Additionally, the exclusion of the private sector from reservation mandates limits broader economic mobility. Beyond quantitative gains, systemic barriers like caste-based discrimination and social stigma continue to hinder genuine empowerment. The study also examines key challenges, including corruption in caste certification, political instrumentalization, and the tension between meritocracy and social justice. To strengthen the reservation framework, the paper proposes policy reforms such as integrating economic criteria, expanding skill development programs, and enforcing anti-discrimination laws in private employment. Ultimately, while reservations have been transformative, their future success depends on adaptive policies that address evolving inequalities while staying true to the constitutional vision of equity and justice.

Keywords: Caste-Based Reservation, Scheduled Castes, Creamy Layer, Socio-Economic, Discrimination.

I. INTRODUCTION:

The caste system, a deeply entrenched social hierarchy in India, has historically dictated social standing, occupation, and access to resources based on birth. This rigid system perpetuated profound social and economic inequalities, with individuals from lower castes, particularly Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, facing systemic discrimination and marginalization. The Indian Constitution, adopted in 1950, recognized the need to address these historical injustices and promote social justice through affirmative action. The constitutional basis for caste-based reservations is enshrined in Articles 15(4), 16(4), and 46 [4], which empower the state to make special provisions for the advancement of SCs, STs, and Other Backward Classes. The initial aim of the reservation policy was to redress historical disadvantages and create a more equitable society by providing these groups with enhanced access to education and employment opportunities in the public sector. This policy, arguably the world’s largest and most extensive affirmative action initiative [7], aimed to level the playing field and enable social mobility for historically disadvantaged communities. However, the policy’s implementation has been fraught with challenges, and its effectiveness and fairness remain subjects of ongoing debate and contention, [7]. This paper will critically examine the impacts, challenges, and potential pathways for reform of India’s caste-based reservation policy.

II. EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE ON THE IMPACTS OF CASTE-BASED RESERVATIONS:

The impact of caste-based reservations on human development is a complex and multifaceted issue, with a large body of research offering both positive and negative findings. Studies assessing the policy’s effects on educational attainment, employment opportunities, and socio- economic status have yielded varied results, highlighting the need for a nuanced understanding of its impact across different castes, regions, and time periods. The long-standing nature of the policy and the multitude of factors influencing social mobility make it challenging to isolate the specific effects of reservations,[8]. This section will critically analyze existing empirical evidence, acknowledging the complexities inherent in evaluating such a broad and long-term intervention.

A. EDUCATIONAL ATTAINMENT:

Reservations have undoubtedly increased the representation of SCs and STs in higher education institutions [12] [4], found a declining gap between Dalits, Adivasis, and other groups in the odds of completing primary school, suggesting a positive impact at the primary education level. However, the same study found little improvement in inequality at the college level. This disparity might indicate limitations in access to higher education or other systemic barriers that prevent SCs and STs from fully benefiting from the reservations provided at the higher education level [6]. Furthermore, concerns remain about the potential for a “Creamy Layer” effect, where higher-income individuals within SC and ST communities disproportionately benefit from reservations at the expense of their poorer counterparts [12]. This concern highlights the need for more targeted interventions that specifically address the needs of the most disadvantaged within these communities. Further research is needed to assess the quality of education received by those benefiting from reservations and to identify specific barriers that hinder educational attainment beyond access to higher education institutions. The impact of reservation policies on educational attainment needs to be analyzed not just in terms of access but also in terms of quality and outcomes.

B. EMPLOYMENT AND ECONOMIC OPPORTUNITIES:

The impact of caste-based reservations on employment opportunities is another crucial area of investigation, [7] found that employment quotas significantly affected the occupational choices of SCs and STs during the 1980s and 1990s, with SC individuals being more likely to choose high-skill occupations. However, the impact of quotas was also related to an individual’s years of schooling, suggesting that education remains a crucial determinant of employment outcomes. The study’s findings suggest that while reservations can influence occupational choices, they may not fully address the underlying inequalities that limit economic opportunities for these communities [7], [3], estimated that the boost provided by reservation policies was around 5 percentage points, but also pointed out that an alternative, more effective way to improve the proportion of SC/ST men in employment would be to improve their employment-related attributes. This highlights the limitations of reservations as a standalone solution. Moreover, the private sector, which employs a significantly larger portion of the workforce, is largely unaffected by reservation policies, leading to continued discrimination against SCs and STs in this sector [7], addressing this requires a multi-pronged approach, including tackling discrimination in the private sector and strengthening the enforcement of anti-discrimination laws. Further research should also investigate the long-term impact of reservations on employment stability and wage levels for SCs and STs.

C. SOCIO-ECONOMIC STATUS AND WELL-BEING:

The effect of caste-based reservations on overall socio-economic status and well-being is a complex issue, with limited conclusive evidence. While reservations have increased representation in education and government jobs, their impact on poverty rates, health outcomes, and access to basic services remains inconclusive [4], [7]. Studies often struggle to isolate the impact of reservations from other factors influencing socio- economic outcomes, such as economic growth, government policies, and social changes. Furthermore, using socio-economic indicators alone may not fully capture the impact of reservations on social inclusion and empowerment. While improved access to education and employment can lead to improved socio-economic outcomes, it is equally important to consider the impact of reservations on social attitudes, discrimination, and the overall social inclusion of SCs and STs. Qualitative studies exploring the lived experiences of individuals from these communities are crucial for understanding the broader societal impact of reservations. Future research should focus on developing more comprehensive measures of well-being that incorporate social inclusion, empowerment, and the reduction of social stigma, in addition to traditional socio-economic indicators.

FIG.1: CASTE-BASED RESERVATION IMPACTS:

III. CHALLENGES AND CRITICISMS OF CASTE-BASED RESERVATIONS:

Despite the laudable intentions behind the reservation policy, it has faced significant challenges and criticisms. One major criticism center on the principle of meritocracy, with concerns that reservations may compromise the selection of the most qualified candidates for education and employment opportunities, [7]. This criticism often ignores the historical and systemic disadvantages that have prevented SCs and STs from competing on an equal footing. The policy’s implementation has also been criticized for potentially fostering social division and resentment between reserved and unreserved categories, [12]. The perception of unfairness and the potential for reverse discrimination can undermine social cohesion and create tensions within society. Moreover, the effectiveness of quotas as a tool for comprehensive social transformation is questioned, [7]. While reservations have increased representation in certain sectors, they have not fully eradicated caste-based discrimination or addressed the underlying structural causes of inequality. The “creamy layer” effect, where higher-income individuals within reserved categories disproportionately benefit, further exacerbates concerns about equity and effectiveness [12]. The complexities of implementing and enforcing the policy, including instances of manipulation and sabotage, also pose significant challenges [12], [7]. These challenges highlight the need for policy reforms and complementary interventions to address the limitations of caste-based reservations.

IV. ALTERNATIVE APPROACHES AND POLICY REFORMS:

Given the challenges associated with the current reservation policy, exploring alternative approaches and policy reforms is crucial. While reservations have played a significant role in increasing access to education and employment, they are not a panacea for caste-based inequalities. Alternative policy designs could include means-tested programs that provide financial assistance based on need rather than caste, scholarships targeting specific academic needs or financial hardship, and targeted interventions aimed at addressing specific needs within disadvantaged communities. These targeted interventions could focus on skill development, entrepreneurship training, and addressing specific barriers to access to education and employment. A combination of different approaches, tailored to the specific context and needs of different communities, could potentially maximize the impact of affirmative action. Moreover, addressing the underlying social and economic barriers that perpetuate caste-based inequalities is essential, [7]. This might involve initiatives promoting social inclusion, addressing discrimination in the private sector, and strengthening the enforcement of anti-discrimination laws. A holistic approach that combines reservations with other complementary interventions could lead to more effective and equitable outcomes. Furthermore, regular monitoring and evaluation are crucial to assessing the effectiveness of different approaches and to making necessary adjustments based on evidence.

V. POLITICAL DIMENSIONS AND SOCIETAL IMPACTS:

Caste-based reservations have significant political dimensions, influencing electoral politics, party politics, and power dynamics within villages [2], [10], [5]. The reservation of seats in local governments has altered political representation, increasing the participation of SCs and STs in the political process [2], [5]. However, studies have also shown that this increased representation does not always translate into improved service delivery or equitable distribution of resources within villages [2]. The impact of reservations on party politics is also complex, with some arguing that it has strengthened caste-based political mobilization and potentially exacerbated social divisions [8]. At the village level, the impact of reservations on power dynamics can be multifaceted, with potential benefits for targeted groups but also the possibility of elite capture or manipulation of resources [2]. The broader societal impacts of the policy extend beyond the political realm, shaping social identities, influencing social norms and attitudes, and potentially contributing to either social cohesion or division [9], [11], [10]. The long-term impact of reservations on social attitudes and the persistence of caste-based discrimination requires further investigation. Understanding the political and societal impacts of reservations is crucial for designing effective and equitable policies.

FIG 2: UNPACKING THE IMPACTS OF CASTE-BASED RESERVATIONS

VI. CASE STUDY:

This case study examines public perception around caste-based reservation policies in India through a structured survey. The survey covers opinions of students, working professionals, and marginalized communities. It highlights growing support for economic-based reservations and dissatisfaction with the current quota system. The case study synthesizes insights from a survey of 324 respondents through online mode from urban and semi-urban areas between the age of below 18–above 50, conducted to gauge public perception on caste-based reservations. Attached below are pie charts, bar graphs, and line charts that provide insights into various questions related to caste-based reservation.

Fig 3: Age

The bar graph in figure-3 represents the age distribution of 324 survey respondents regarding their views or experiences related to caste-based reservation policies in India. Here’s a breakdown of the data: The 18–25 age group has the highest number of respondents (likely 100–120), indicating strong engagement from younger adults (students or early-career individuals). The 26–35 and 36–50 age groups show moderate participation (around 60–80 each), suggesting working professionals or middle-aged individuals contributed significantly. The Below 18 and Above 50 groups have the lowest responses (below 40), possibly due to limited accessibility (minors) or lower survey outreach to older demographics. The survey reflects strong youth engagement with caste-based reservation, underscoring its contemporary relevance in shaping opportunities for marginalized communities.

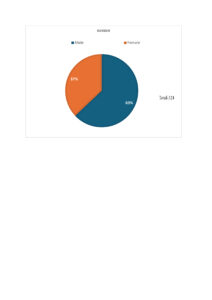

FIG 4: GENDER RATIO

The pie chart in figure-4 illustrates the gender composition of the 324 respondents who participated in a survey regarding caste-based reservation policies. Out of the total 324 participants: 63% were Male and 37% were Female. A significant majority of the participants (63%) are male, indicating higher male engagement or representation in the survey. This may suggest that men were either more accessible for the survey or more interested in expressing their opinions on the topic of caste-based reservation. Although comparatively lower, female participation stands at 37%, which is still a considerable portion. It reflects that women’s voices are also present in the conversation around reservation policies, though they may be underrepresented. This Gender-based analysis of opinions can help in understanding if and how perceptions toward reservation differ between men and women.

FIG 5: EDUCATION QUALIFICATION

The line chart in figure-5 presents the educational background of 324 respondents who participated in the survey related to caste-based reservation. A large portion of participants are either postgraduates (51%) or undergraduates (42%), indicating that the majority of survey responses come from individuals with higher educational backgrounds. The highest number of responses came from postgraduates, which could imply that individuals with deeper academic exposure are more engaged or interested in the subject of caste-based reservations. Very few respondents are from below 12th (1.5%) or doctorate level (6%), which shows minimal representation from the extremes of the educational spectrum. Since most responses are from well-educated individuals, the survey likely reflects more informed or analytical views on reservation policies. The data suggests a lack of representation from less-educated individuals, whose voices are also crucial when discussing reservations meant to support socio-educational equity.

FIG 6: EMPLOYMENT STATUS

The bar graph shows the employment distribution of the 324 individuals who participated in the caste-based reservation survey. The largest group in the survey (approximately 37.3%) is government-employed individuals, indicating significant interest or concern from people directly connected to state policy and reservation benefits while Students make up nearly 24.7% of the respondents. This is a crucial demographic, since caste-based reservation policies often impact admissions and educational opportunities directly. Together, private sector employees and self-employed individuals account for about 31% of the responses. Their perspectives may reflect views on how reservations affect employment and economic competition outside the government sector. Only 23 respondents (7.1%) are unemployed, which may indicate limited accessibility or willingness among unemployed individuals to participate in the survey. The dominance of government employees and students in the survey means the data will heavily reflect the views of those directly impacted by reservation policies in jobs and education. The diverse range of employment statuses allows for comparative analysis between how different groups perceive the effects and fairness of caste-based reservations.

FIG 7: CATEGORY OF INDIVIDUALS

This line chart reflects the caste-based self-identification of the 324 individuals who participated in the survey. The General category dominates the sample with 200 respondents (61.7%), showing a strong representation of individuals who are typically not direct beneficiaries of caste-based reservations. OBC respondents make up 18.8%, reflecting fair representation of a group that benefits from reservation. SC respondents (13%) are also notably present, offering a valuable insight into how beneficiaries perceive the system. Only 7 respondents identified as ST (Scheduled Tribes), which is just about 2.2% of the total. This indicates underrepresentation of tribal voices in the survey. Very few participants chose “Prefer not to say” (8) or gave no answer (1), suggesting most respondents were comfortable disclosing their caste identity. A small number of people identified themselves under “Other” (3 respondents), which might include mixed caste backgrounds or unrecognized categories. For a more balanced understanding of caste-based reservation impact, it is essential to increase participation from SC, ST, and OBC categories in future studies. With representation from both beneficiary and non-beneficiary categories, this dataset offers a chance to compare and contrast perceptions across caste lines.

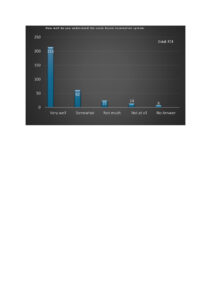

FIG 8: UNDERSTANDING CASTE-BASED RESERVATION SYSTEM

This bar graph illustrates the participants’ self-assessed understanding of how well they comprehend the caste-based reservation system. A significant majority — 215 out of 324 respondents (66.3%) — claim they understand the reservation system very well. This indicates that the topic is well-known and commonly discussed in society, especially among educated or socially aware groups. About 19.1% (62 respondents) stated they understand it somewhat, suggesting some exposure but possibly lacking detailed knowledge of the structure, criteria, or implementation. 25 respondents (7.7%) said they do not understand much, while 14 respondents (4.3%) admitted to having no understanding at all. This highlights a small but important portion of the population that may form opinions without a clear understanding of the policy. Only 8 respondents (2.5%) didn’t answer or chose not to respond to this question, showing that most participants were comfortable sharing their level of awareness. The large percentage of well-informed participants strengthens the credibility and relevance of the survey findings, as these responses are likely based on actual understanding rather than assumptions. With over 85% of respondents claiming to understand the system either very well or somewhat, the dataset enables an in-depth analysis of opinions from people who are more likely to provide informed perspectives. Although small in number, the existence of people with little or no understanding suggests there is still a need to raise awareness and provide simplified information about the reservation system, especially for inclusive public discourse.

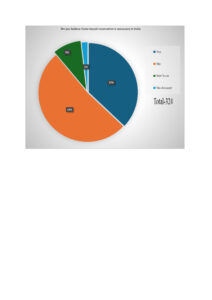

FIG 9: NECESSITY OF CASTE-BASED RESERVATION

This pie chart reflects the public opinion on whether caste-based reservation is still necessary in India today. A majority (52%) of respondents believe that caste-based reservation is not necessary in present-day India. This suggests that more than half of the participants may feel that the policy has either served its purpose or has become outdated, possibly favoring a merit-based or economically-driven alternative. Despite the opposition, a considerable proportion — 37% of respondents — believe that caste-based reservation is still necessary. This reflects ongoing societal acknowledgment of caste-based inequalities and the role of reservation in correcting historical disadvantages. Only 2.8% of respondents were not sure, and a minimal number chose not to answer. This shows that the issue is highly debated and that most individuals already have a formed opinion. The results reflect a clear division in public opinion, suggesting that caste-based reservation remains a controversial and emotionally charged issue in India. Any policy reforms in this area may face significant resistance or support depending on how they align with these polarized views. The presence of both strong support and strong opposition highlights the need for inclusive policy discussions, awareness campaigns, and more nuanced public debates — especially considering regional, social, and economic contexts. Since over half of the participants believe that caste-based reservation is no longer necessary, policymakers might consider reassessing the criteria or implementation of reservation — possibly incorporating economic, regional, or educational backwardness alongside or instead of caste.

FIG 10: IMPLEMENTATION OF RESERVATION IN DIFFERENT SECTORS

This bar graph represents the public opinion on where reservation should be applied, if at all. A significant portion of respondents support reservation in the education sector, indicating a belief that reservation should help uplift underrepresented communities through access to learning and knowledge. It reflects the idea that equal opportunity begins with education. Many still believe that government employment should provide reserved opportunities to support marginalized groups. This is aligned with traditional reservation policies already prevalent in India. A large group of respondents (nearly 31%) believe that no form of reservation should exist. This could stem from concerns about meritocracy, reverse discrimination, or the belief that caste-based reservation has outlived its relevance. There is limited support for extending reservation into the private job market or political space. This suggests either reluctance to interfere with private enterprise or skepticism about reservation’s role in political representation. The highest number of responses favoring education implies a general consensus that empowerment through learning is more acceptable and sustainable than job-based quotas. With nearly equal emphasis on education and government jobs (178 total) and those saying “no reservation” (99), the society appears divided between reforming and abolishing reservation. Policymakers might reconsider the extent and sectors of reservation, focusing more on educational access and reform rather than expanding into politics or private employment. Limited support for reservation in private jobs and politics shows public hesitation about interfering with market dynamics or political balance through caste-based policies.

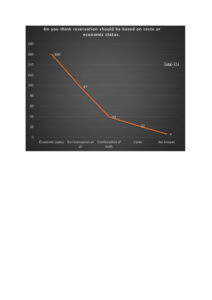

FIG 11: BASES OF RESERVATION: CASTE OR ECONOMIC

This line chart presents the results of a survey on whether people think reservations should be based on caste or economic status. The total number of respondents is 324, and the survey data clearly indicates a shift in public opinion regarding the basis of reservation policies. A majority of respondents (49%) believe that economic status should be the primary criterion for reservation, reflecting a demand for more merit-based and financially inclusive affirmative action. Meanwhile, about 30% oppose any form of reservation, showcasing rising dissatisfaction or belief in equal opportunity without quotas. Only a small minority support caste-based reservation (7%), highlighting changing attitudes toward traditional social structures. The preference for a combination of caste and economic status (12%) indicates a small but present recognition of the complexity of social inequality.

FIG 12: CASTE BASED HELPED IN UPLIFTMENT

This pie chart represents the responses to the question:

“Do you think caste-based reservation has helped uplift disadvantaged communities?”.

The survey reveals a nuanced public opinion on the effectiveness of caste-based reservation in uplifting disadvantaged communities. While 71% of respondents believe that it has had at least some positive impact (40% to some extent and 31% significantly), there is also notable skepticism. About 22% of participants feel that it has not been effective, pointing to dissatisfaction with its outcomes or implementation. Meanwhile, 5% remain unsure, and 2% chose not to respond. These findings suggest that while the policy is broadly seen as beneficial, there is considerable debate about the extent of its success and its future direction.

FIG 13: RESERVATION SHOULD BE GRANTED ON BASED ON SOCIO-ECONOMIC DATA.

This bar graph shows survey responses to the question:

“Should reservation policies be revised periodically based on socio-economic data?”

In the survey, an overwhelming 80% of respondents believe that reservation policies should be revised periodically based on socio-economic data, signaling a strong call for modernization and evidence-based policy-making. Only a small minority (7%) opposed this idea, while 9% were unsure. These results clearly highlight a public preference for adaptable and responsive systems that better align with the current socio-economic landscape, rather than relying solely on historical classifications.

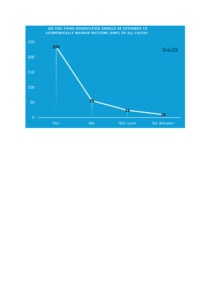

FIG 14: RESERVATION SHOULD BE EXTENDED TO EWS

This line chart reflects responses to the question:

“Do you think reservation should be extended to Economically Weaker Sections (EWS) of all castes?”.

Hence the data strongly suggests that public sentiment favors extending reservation benefits to economically weaker sections (EWS) of all castes, with 72% of respondents supporting the idea. This reflects a growing inclination toward economic-based affirmative action, emphasizing the need to address poverty and inequality across all social groups. Meanwhile, 17% opposed this expansion, and 7% were unsure. These results highlight the evolving perception of reservation policies as tools not just for historical redress, but also for economic upliftment across the board.

FIG 15: CASTE-BASED RESERVATION AFFECTS MERITOCRACY IN INDIA.

This pie chart presents responses to the question:

“Do you think caste-based reservation affects the meritocracy in India?”

From this the data shows that 59% of respondents feel caste-based reservation negatively impacts meritocracy in India, indicating concern over fairness and performance-based systems. In contrast, 28% believe reservation helps create equal opportunities, suggesting support for its role in addressing historical social imbalances. Meanwhile, 11% remain unsure, and 2% did not answer. These findings highlight a significant divide in public opinion, with many questioning the balance between equity and merit in the current reservation framework.

FIG 16: ENTRANCE EXAMS AND JOBS RECRUITMENT HAVE A UNIFORM SELECTION PROCESS WITHOUT ANY RESERVATION

This bar graph shows responses to the question:

“Should entrance exams and job recruitments have a uniform selection process without any reservation?”.

The graph reflects public opinion on whether the current reservation-based system in exams and recruitment should be replaced with a uniform, merit-based selection process. A clear majority (220 out of 324) believes that entrance exams and job recruitment should be based solely on merit, without any form of reservation. This reflects growing support for a level playing field where selection is based on performance, not background. A smaller portion (16%) believes that reservation should remain in the selection process, possibly recognizing its role in correcting historical disadvantages and providing equitable access. A considerable number of respondents (13%) are uncertain, suggesting that public opinion is still evolving. This group may see merit in both systems or feel under-informed. Very few (3%) skipped the question, showing that most participants had a definite opinion, indicating the importance and relevance of the issue in public discourse. Hence there is a significant demand for reform in how selection processes are conducted, with a clear lean toward meritocracy. Policymakers must carefully balance public opinion with social justice obligations, possibly considering alternative frameworks like financial need–based support or a gradual transition from caste to economic criteria.

FIG 17: SUGGESTION FOR RESERVATION SYSTEM

The bar graph captures the diverse range of public opinions gathered through a survey question:

“What changes would you suggest to India’s reservation system?”

From this a total of 324 respondents provided their views, reflecting a strong interest in reassessing the current caste-based reservation framework. Here under there is the key suggestions which are as follows:

1. Shift to Economic Status (EWS) – 120 responses (37%) The most popular suggestion is to base reservation on economic status, particularly targeting Economically Weaker Sections (EWS) across all castes. This aligns with the growing public opinion that financial hardship is a more relevant criterion than caste in today’s context.

2. Abolish Caste-Based Reservation – 85 responses (26%) A significant portion of respondents favor scrapping caste-based reservation entirely, possibly due to concerns about fairness, misuse, or outdated relevance.

3. Merit-Only System – 62 responses (19%) A considerable number prefer a system based solely on merit, emphasizing equal competition without any affirmative advantage.

4. Reforms (Creamy Layer / Transparency) – 45 responses (14%) There’s also a demand for better regulation, like excluding the “creamy layer” (wealthier sections within reserved categories) and ensuring more transparency.

5. Reservation in Education Only – 38 responses (12%) Some suggest limiting reservation to education only, avoiding its extension into jobs or promotions.

6. Periodic Review / Sunset Clause – 30 responses (9%) Suggests the reservation system should be reviewed periodically and not be indefinite—possibly updated based on new data.

7. Private Sector Inclusion – 14 responses (4%) A few believe reservation should be extended to the private sector, where it currently doesn’t apply.

8. No Change Needed – 9 responses (3%) A small minority think the current system is fine as it is.

9. Other/Unclear – 26 responses (8%) These responses either didn’t clearly fit into a category or suggested varied ideas.

According to the survey, 37% of respondents believe the reservation system should shift focus to economic status (EWS), while 26% favor completely abolishing caste-based quotas. A significant number also support merit-based selection (19%) or reform within the current system (14%). Suggestions like limiting reservation to education, introducing periodic reviews, or including the private sector also appear, though less frequently. Only a small minority believe no changes are needed, indicating a broad consensus for reform and modernization of the reservation policy.

VII. INTERPRETATION OF CASE STUDY:

This study sought to understand contemporary public perceptions regarding caste-based reservation in India by analyzing responses from a structured survey involving 324 participants across urban and semi-urban areas. The sample included a wide demographic spread in terms of age, gender, education, employment, and caste identity, allowing for a multifaceted analysis of opinions.

1. Demographic Distribution and Engagement: A significant portion of the respondents were in the age group of 18–25, indicating heightened awareness and concern about reservation policies among youth. With 51% postgraduates and 42% undergraduates, the data reveals that individuals with higher educational qualifications are more engaged in policy-related discourse. Gender distribution was skewed toward males (63%), potentially due to accessibility or interest levels, but the female participation (37%) still reflects a fair degree of inclusivity. Employment-wise, the dominant groups included government employees (37.3%) and students (24.7%), who are direct stakeholders in the reservation system.

2. Caste Representation and Understanding: An overwhelming 61.7% of participants identified as belonging to the General category, with OBC (18.8%) and SC (13%) following behind. STs were underrepresented (2.2%), suggesting the need for broader outreach in future research to include more voices from tribal communities. Importantly, 66.3% of respondents reported having a very good understanding of the reservation system, enhancing the reliability of their perspectives.

3. Contemporary Relevance and Necessity of Reservation: Notably, 52% of respondents opined that caste-based reservation is no longer necessary in modern India. This suggests a rising inclination toward merit-based or economic criteria for affirmative action. However, 37% still support its continuation, indicating that caste-based inequalities persist in public consciousness. The presence of this divide underlines the ongoing tension between social justice imperatives and meritocratic ideals.

4. Sectoral Preference and Scope for Reform: Support for reservation in education and government employment remains significant, reflecting traditional sectors of reservation policy. However, nearly 31% of respondents opposed any form of reservation, and support for extending reservation to the private sector or politics was minimal. This suggests a societal preference for limiting affirmative action to public institutions and educational upliftment rather than expanding it into new sectors.

5. Shift Toward Economic-Based Reservation: A majority of respondents (49%) favored an economic criterion for reservation, while only 7% supported caste-based criteria alone. This trend signifies a paradigm shift in public opinion toward financially inclusive affirmative action. The support for a combined model (12%) indicates a nuanced understanding of the intersection between caste and class disadvantages.

6. Perceived Impact and Challenges of Reservation: While 71% of respondents acknowledged some positive impact of caste-based reservation on marginalized communities, 22% felt it has failed to uplift them, and 5% remained uncertain. Additionally, 59% believed that caste-based reservation affects meritocracy negatively, while only 28% viewed it as a means to ensure equal opportunity. These findings reflect deep-seated ambivalence in public perception and suggest a need to balance social equity with individual competence in policy implementation.

7. Policy Revision and Future Direction: An overwhelming 80% of participants supported periodic revisions of reservation policies based on current socio-economic data. Furthermore, 72% favored extending benefits to Economically Weaker Sections (EWS) of all castes, reinforcing the push for a needs-based rather than identity-based framework. When asked about changes needed, 37% recommended shifting to EWS criteria, 26% supported abolition of caste-based quotas, and 19% called for a merit-only system. These responses reveal strong support for reform and modernization, with an emphasis on fairness, periodic review, and socio-economic equity.

VIII. SUGGESTIONS:

The survey demonstrates a strong public consensus in favor of reforming the reservation system. The largest support lies with shifting the basis to economic need, followed by abolishing caste-based quotas or introducing a merit-only framework. Even among those not in favor of total abolition, many call for internal improvements, transparency, and time-bound implementation, indicating a desire for modernization rather than status quo. The responses reveal that reservation is still a relevant issue, but public expectations have evolved, and policymakers need to adapt reservation policies to match new social realities. Here under there are some suggestions for reservation policies.

1. Move Toward Economic-Based Reservation: Contemporary public opinion increasingly supports a shift from purely caste-based to economic-based criteria in the allocation of reservations. This suggests a growing belief that financial hardship, irrespective of caste, is a more accurate measure of disadvantage in today’s socio-economic landscape. Integrating economic status into the reservation framework could enhance targeted support, ensuring that benefits reach individuals who are genuinely marginalized due to poverty, thus increasing both the fairness and efficacy of affirmative action policies.

2. Hybrid Model of Reservation: Rather than an either/or approach, a hybrid model that incorporates both caste and economic indicators may prove more equitable. Such a model acknowledges historical and systemic oppression while also recognizing contemporary economic disparities. By doing so, it offers a balanced mechanism for redressal, catering to both the legacy of social exclusion and current economic vulnerability. This dual approach may help bridge ideological divides between traditional supporters of caste-based reservations and those advocating for economic criteria.

3. Phase-wise Review of Existing Policies: A dynamic policy review mechanism is essential to maintain the relevance of reservation systems. Periodic, phase-wise evaluations—guided by empirical data, stakeholder feedback, and evolving social metrics—can help identify redundancies, unintended consequences, and emerging needs. Such a review process would align reservation policies with changing societal structures and expectations, allowing for data-driven reform rather than static adherence to outdated models.

4. Promote Merit with Support Mechanisms: To uphold academic and professional excellence, it is critical to ensure that affirmative action does not compromise merit. A reimagined support structure—comprising scholarships, preparatory coaching, mentorship, and capacity-building programs—can empower underprivileged individuals without relying solely on quotas. This approach preserves the integrity of meritocracy while still offering the disadvantaged meaningful avenues for advancement.

5. Enhance Awareness and Transparency: Findings from the research indicate a significant level of dissatisfaction and confusion among the public regarding reservation policies, often stemming from lack of clarity and perceived inequities. Improving transparency in implementation and enhancing public awareness about the rationale, scope, and benefits of reservations can foster greater trust and legitimacy. Educational campaigns and accessible communication can play a key role in demystifying the system and reducing misinformation.

6. Address Reservations in Private Sector and Promotions Cautiously: The extension of reservations into private employment and promotional hierarchies is a contentious issue. While it could potentially broaden social inclusion, it must be approached with caution, considering the readiness of the private sector, possible economic repercussions, and the perception of reverse discrimination. Pilot studies and stakeholder consultations are essential before broader implementation to prevent backlash and ensure a balanced integration.

7. Focus on Upliftment Without Stigma: One of the unintended effects of reservation policies can be the social stigma attached to beneficiaries. Policy design should strive to de-stigmatize affirmative action by focusing on inclusive language, anonymous support mechanisms, and confidence-building measures. By shifting the narrative from charity to empowerment, reservation policies can promote a sense of dignity and social cohesion, enabling beneficiaries to thrive without feeling labeled or marginalized.

IX. CONCLUSION: THE PATH FORWARD AND FUTURE RESEARCH DIRECTIONS:

Caste-based reservations in India represent a complex and multifaceted policy with both successes and limitations. While reservations have undeniably increased the representation of SCs and STs in education and employment, they have not fully eradicated caste-based inequalities or addressed the underlying structural causes of discrimination. The policy’s effectiveness and equity remain subjects of ongoing debate, highlighting the need for critical evaluation and potential reforms, [7], [4]. The path forward requires a multi-pronged approach that combines targeted interventions with broader efforts to address systemic inequalities. This might involve means-tested programs, scholarships, skill development initiatives, and measures to combat discrimination in the private sector. Moreover, strengthening the enforcement of anti-discrimination laws and promoting social inclusion are crucial. Ongoing monitoring and evaluation are essential to assess the effectiveness of different approaches and make necessary adjustments based on evidence, [12]. Future research should focus on several key areas, including the long-term impacts of reservations on different aspects of social and economic life, the effectiveness of different policy designs, and the dynamics of social inclusion and empowerment within reserved communities. Qualitative studies exploring the lived experiences of individuals from SC and ST communities are also crucial for a more nuanced understanding of the policy’s impact. By adopting a comprehensive and evidence-based approach, India can strive towards a more just and equitable society, addressing both the immediate needs of marginalized communities and the underlying structural causes of inequality, [7].

Cite this article as:

ANMOL JASROTIA & SOMBIR GULIA & GARIMA DEEKSHA CHANDANI, “Reassessing Caste-Based Reservation In India: Impacts, Challenges and The Path Forward” Vol.5 & Issue 6, Law Audience Journal (e-ISSN: 2581-6705), Pages 433 to 464 (27th April 2025), available at https://www.lawaudience.com/reassessing-caste-based-reservation-in-india-impacts-challenges-and-the-path-forward/.

ANMOL JASROTIA & SOMBIR GULIA & GARIMA DEEKSHA CHANDANI, “Reassessing Caste-Based Reservation In India: Impacts, Challenges and The Path Forward” Vol.5 & Issue 6, Law Audience Journal (e-ISSN: 2581-6705), Pages 433 to 464 (27th April 2025), available at https://www.lawaudience.com/reassessing-caste-based-reservation-in-india-impacts-challenges-and-the-path-forward/.

References:

1. Alsop, R., & Heinsohn, N. (2005). Measuring empowerment in practice: Structuring analysis and framing indicators. https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-3510.

2. Bardhan, P., Mookherjee, D., & Torrado, M. P. (2010). Impact of political reservations in West Bengal local governments on anti-poverty targeting. Economics and Politics, 22(3), 409–436. https://doi.org/10.2202/1948-1837.1025.

3. Borooah, V. K., Dubey, A., & Iyer, S. (2007). The effectiveness of jobs reservation: Caste, religion, and economic status in India. Development Policy Review, 25(5), 553–572. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7660.2007.00418.x.

4. Chalam, K. S. (2007). Caste-based reservations and human development in India.

5. Gulzar, S., Haas, N., & Pasquale, B. (2020). Does political affirmative action work, and for whom? Theory and evidence on India’s Scheduled Areas. American Political Science Review, 114(4), 1141–1158. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0003055420000532.

6. Gupta, A. (2006). Affirmative action in higher education in India and the US: A study in contrasts (CSHE.10.06).

7. Howard, L. L., & Prakash, N. (2011). Do employment quotas explain the occupational choices of disadvantaged minorities in India? Education Economics, 19(5), 495–513. https://doi.org/10.1080/02692171.2011.619969.

8. Jeffrey, C., Jeffery, P., & Jeffery, R. (2008). Dalit revolution? New politicians in Uttar Pradesh, India. Modern Asian Studies, 42(4), 989–1011. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021911808001812.

9. Jodhka, S. S. (2015). Ascriptive hierarchies: Caste and its reproduction in contemporary India. Current Sociology, 63(3), 393–411, https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392115614784.

10. Munshi, K., & Rosenzweig, M. R. (2008). The efficacy of parochial politics: Caste, commitment, and competence in Indian local governments. https://doi.org/10.3386/w14335.

11. OHanlon, R. (2017). Caste and its histories in colonial India: A reappraisal. Modern Asian Studies, 51(2), 321–351. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0026749x16000408.

12. S, D., & V, K. (2008). Changing educational inequalities in India in the context of affirmative action. Demography, 45(2), 245–270. https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.0.0001.